New Jersey had the 6th largest increase in the country over the last decade or so.

Students who speak or understand little or no English because they use another language at home make up about 10% of America’s public school students. And while the greatest concentration remains along the southern border, they are now about 8% of New Jersey’s public school population.

In districts like Newark, though, it’s much higher: More than a quarter of the student body. It can be a steep learning curve for schools that don’t have the decades of bilingual teaching experience found in states like California.

These students are more likely to attend high poverty, urban schools, and while about 70% speak Spanish in New Jersey, the rest speak a wide variety of languages – most commonly Arabic, Portuguese, Haitian Creole, Chinese and Korean.

So, districts are scrambling to adjust. To understand the challenge, NJ Spotlight News spoke with Karen Thompson, a leading researcher in the subject who spent more than a decade working with these students in California. This transcript was edited for brevity.

NJ Spotlight News: What can you tell us about this latest surge of English learners?

Credit: Courtesy of Karen Thompson

Credit: Courtesy of Karen ThompsonKaren Thompson: Nationally, between one and four or five students speak a language other than English at home, and a little over one in 10 are classified as English learners, meaning they don’t score proficiently in English when they enter school. The vast majority become proficient in English. That’s why a lot more students speak a language other than English at home than are currently classified as “English learners.”

This is not the first time, by any means, that the U.S. has seen increases in English learners. And it’s a myth that all are immigrants. There are children born here, who grew up speaking English and other languages at home, that are classified as English learners for a period in school, as well as newly arrived immigrants.

NJSN: Is it best practice to teach them in their native language until they learn English?

KT: Students in high quality bilingual programs do have more positive outcomes than in English-only programs. The most common form of bilingual education in the U.S. today is dual language education, in which students learn in both their home language and English. The first year might start off 90% in the partner language – for example, Spanish – and 10% of the time in English, with the percentage of Spanish decreasing and percentage of English increasing over the grade levels.

Other models are 50-50 from the beginning. There’s a real range in the research. It’s very difficult to tease out and compare models. A key Supreme Court case in 1974 established two core rights of students classified as English learners: That they have opportunities to learn English, and access to grade level content. So, all programs enrolling English learners in the U.S. must provide those two things.

NJSN: What if a district can’t find enough certified bilingual teachers?

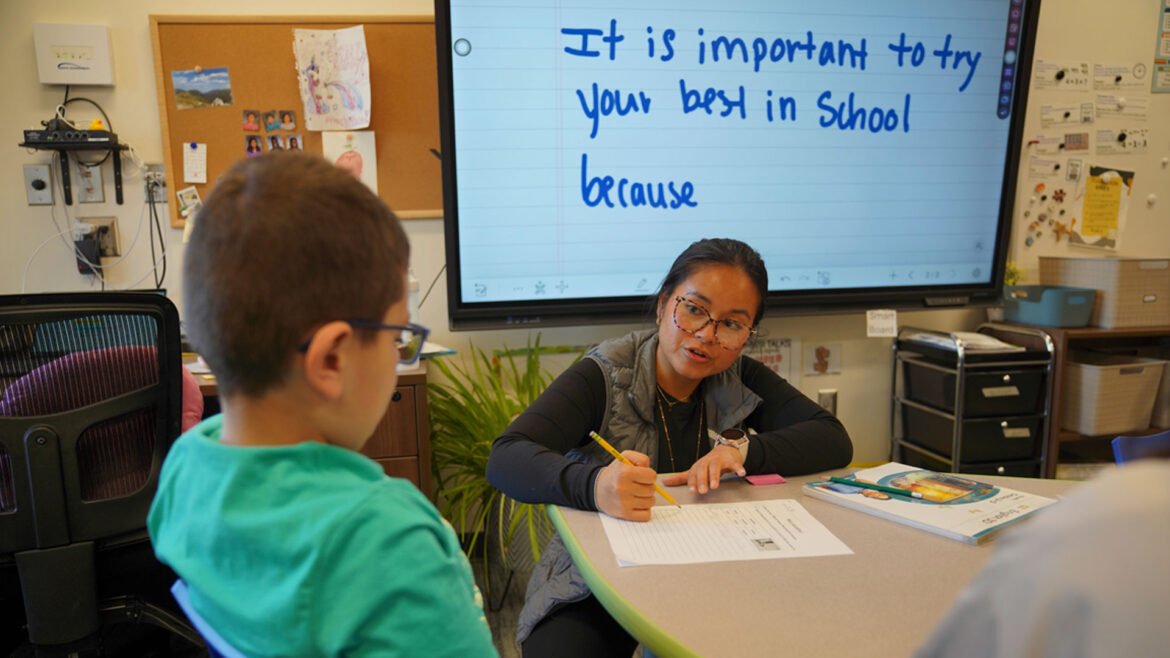

Some just use English-speaking teachers certified in teaching English as a Second Language (ESL). States really vary in the extent of training required for all teachers. Part of what I do in my teacher education role is help teachers – whether it’s an art teacher, a kindergarten teacher, music teacher, or high school math teacher – learn how to work with multilingual students. There are many strategies, such as using visuals.

NJSN: So, an English learner might spend part of the day just learning English, and the rest in regular classes, perhaps with a teachers’ assistant who speaks the same native language and can help?

KT: Districts approach this in many different ways, but yes.

NJSN: Who’s doing a good job on this? You say you observed one innovative model at a middle school in Oregon, in which an ESL teacher was working together with a language arts teacher. Usually, ESL classes are held separately, right?

KT: Yes. And importantly, if the class is separate, students often have to give up a space in their schedule to take ESL. But in this integrated model, they’re getting both at the same time. The two teachers are working together to teach language and content.

As a result, students have space for more content classes and electives. Otherwise, they may feel stigmatized by having to go to a separate, standalone English language development or ESL class, especially if they’ve been receiving these services for quite a few years and want to be able to be in band or science class with their friends.

NJSN: What are examples of districts using their extra state and federal dollars for these kids effectively?

KT: Bilingual teachers are perpetually a shortage area. Districts are often very eager to try to expand recruitment. Some, like Oregon, are establishing “grow your own” programs so they can support their graduates in becoming bilingual teachers and returning to their districts. Other states, like Michigan, used some of their federal COVID relief funds to help more teachers get ESL certification. We’ve also seen an increasing number of schools hiring bilingual counselors and social workers.

NJSN: What effect does an influx of English learners have on a district’s test scores? Do the scores of English learners generally take a hit in the early years, then in later years, catch up to or exceed those of their peers?

KT: Yes, although it depends on the comparison group, the language the assessment is in and whether they’re getting high quality services.

NJSN: Recent research found the presence of more English learners (ELs) does not lower the test scores of their non-EL classmates. Why might that be?

KT: Schools may get additional federal and state funding to support English learners. In addition, strategies that teachers use to help English learners can help other students, too.

NJSN: Are there particular challenges in teaching English learners under the Trump administration?

KT: Absolutely. Students and families simply do not feel safe at school, so we’ve seen increases in absences. We’ve seen whole school systems shut down. Minneapolis closed schools because of immigration enforcement. We know marginalized students suffer the most when schools are closed. That is extremely concerning. How are you going to focus on algebra when you don’t know if your mom is going to be there when you get home? Teenagers who are U.S. citizens have been caught up in immigration enforcement activities here in Oregon. We hear that happening across the country. It is really disruptive.

NJSN: Finally, any thoughts on the growing popularity of bilingual programs among affluent parents?

KT: Fostering bilingualism is wonderful for everyone. It’s great to have language programs that enroll a mix of students, including native English speakers. But it’s important that districts locate bilingual programs in the communities where multilingual learners live. And we need to make sure they’re benefiting those students. Multilingual learners should be the focus of these programs, the ones prioritized.