The extent of the casualties will be difficult if not impossible to quantify, according to several doctors I spoke with, because the influx of cases far exceeded the capacity of many hospitals. Many patients were not admitted, and some who were admitted were not logged in hospital systems. The medical records that do exist have, in some cases, been tampered with or destroyed, either by security forces or hospital workers coöperating with the regime. Medical workers sympathetic to the uprising, meanwhile, have also changed the names and injuries listed on some patients’ medical charts, to protect their identities from authorities.

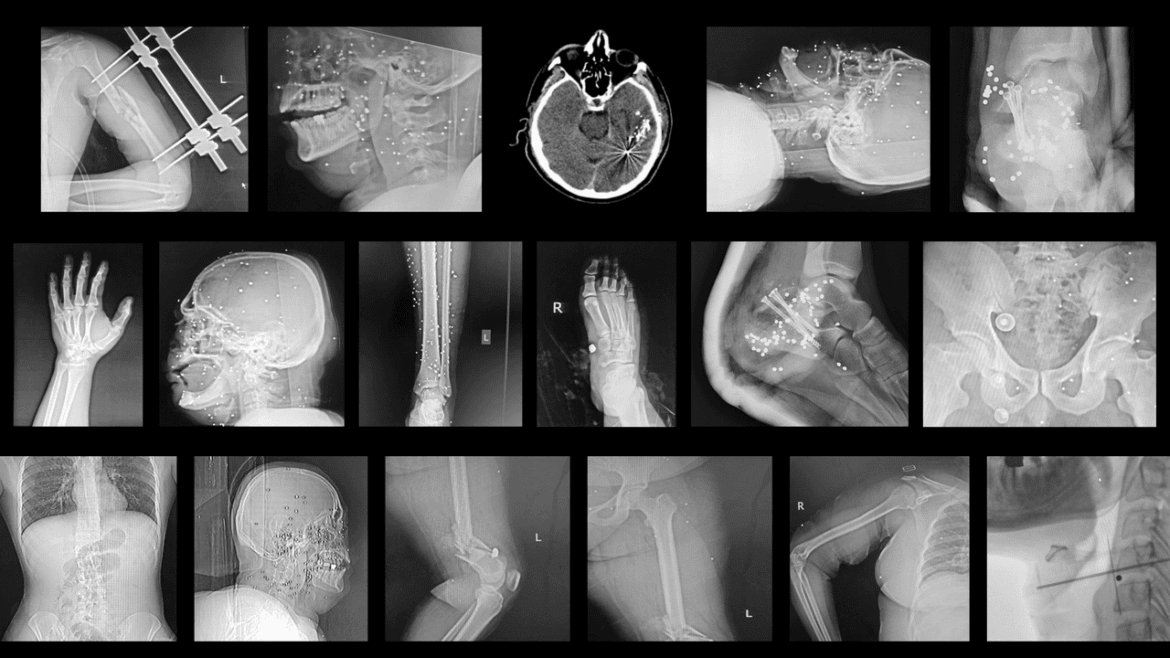

Medical workers have begun quietly doing their own record-keeping. One hospital employee in the northern city of Rasht told me that he had photographed hundreds of pieces of evidence, including CT scans and X-rays, from two emergency wards where he had volunteered during the massacre. “I want the world to know that these people existed, and that they have paid a price for their freedom,” the employee, who I will call Anush, told me. So far, he has collected records for nearly five hundred admitted patients, the majority of whom suffered trauma injuries. The images and scans, which he shared with me, compose an eerie tableau of the dystopian scenes that he witnessed in January: one X-ray showed a bullet that shattered the femur of a forty-seven-year-old mother, who had tried to shield her son from gunfire. One brain scan showed a metal pellet, which had partially blinded a nurse after she was shot in the head while exiting the hospital. “The wards felt like a war zone, run by regime thugs,” Anush said. Agents in plain clothes followed protesters into operating rooms, then detained them when they had completed their medical treatment. On several occasions, Anush said that he saw officers intervene during a surgical procedure, resulting in scuffles with medical staff. A medical intern was hospitalized after he was shot with metal pellets at close range.

He recalled a mother rushing into the ward to show surgeons and nurses a photograph on her phone of her missing son. Soon after she left, officers dragged in a corpse, which “had the face of that mother’s son,” Anush said. He recognized the man easily from the photo she had shown him. “His hands were bound and there was a bullet wound in his head.”

Once it became clear that the emergency wards themselves weren’t safe, “many colleagues started calling in sick—or not showing up for their shifts,” Anush said. He began volunteering at a privately owned clinic, which was filled with injured people. And yet word of the clinic’s existence soon reached security officers, who vandalized it and interrogated the doctor who ran it.

For many of the wounded, the threat of disappearing into Iran’s prisons far outweighs the risks of forgoing medical help. The problem has been especially grim in remote regions, where private clinics are scarce, and patients must travel long distances to get care. Volunteers have organized medical convoys and ferried patients across the country to safe operating rooms.

On a recent January evening, a team of volunteers set out to collect protesters from a city in northern Iran, where they were stranded in their homes with trauma wounds that they had sustained earlier that month. The protesters needed to be transferred to private hospitals, which were better equipped, and where specialists could operate on them. Several of the wounded had bullet holes in their legs or feet. One young woman, who had been struck in the eye by a rubber bullet, was at risk of going blind.

The convoy’s destination was another city, about two hundred miles away. Relatives of the injured drove ahead, in separate cars, and alerted the convoy to checkpoints or police who patrolled intersections along their route. “It was stressful,” one of the volunteers told me. “It was a long drive, and they had a lot of pain.” The driver, nicknamed Renas, tried to keep pace while avoiding potholes. He played music, and sang folk songs to “distract them from their fear—and from mine.” Five hours later, just before sunrise, he delivered the injured to another team of volunteers, who escorted them into safe houses before they could draw attention from police. “I was relieved,” Renas told me. But they did not arrive in time to save the young woman’s eye, which was removed by an ophthalmologist days later. “We are fighting with a wooden spoon,” he said, “against a government that is armed to the teeth.”