Elephants are not exactly commonplace in the European landscape, so when archaeologists uncovered an elephant foot bone among the rubble of an Iron Age dig in Spain, they knew it could be something special.

Based on the bone’s age and where it was found, it might even be the first physical evidence of the Carthaginian general Hannibal’s famous ‘war elephants’.

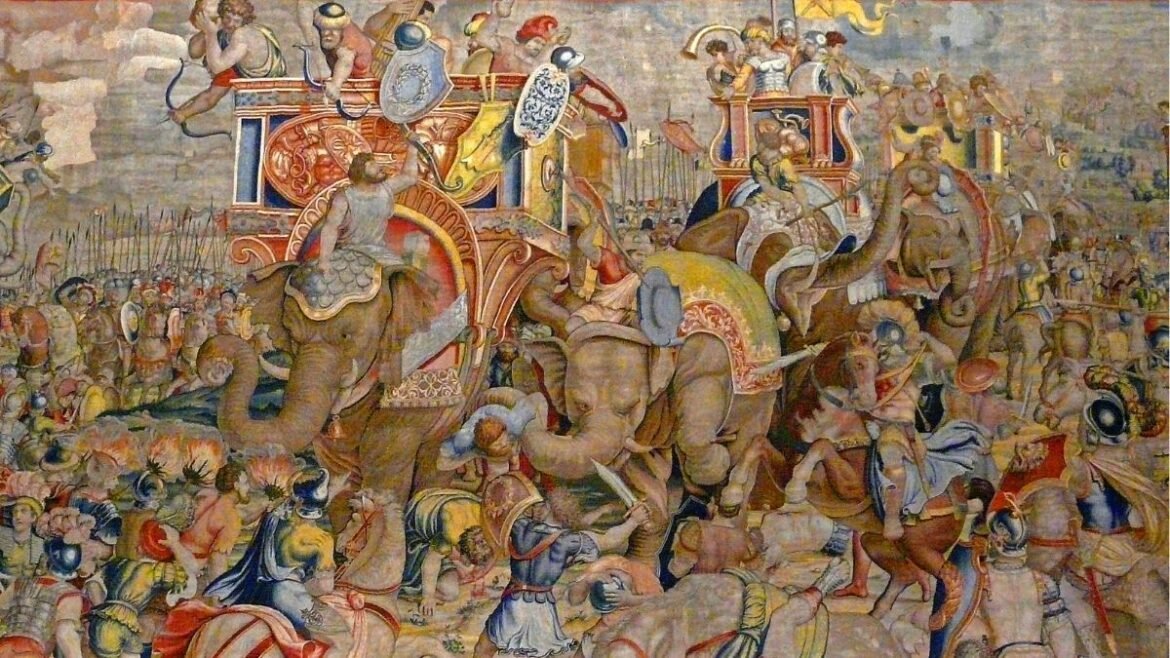

Images of these elephants tromping through a battlefield have been preserved through the centuries in art and literature. But until now, no skeletal evidence of these grand beasts has surfaced.

“The use of elephants as ‘war machines’ on European soil during the Punic Wars left a profound mark on Western art, literature, and culture – a legacy passed down through classical accounts to later authors,” the research team, led by University of Cordoba archaeologist Rafael Martínez Sánchez, explains in their published paper.

Hannibal is said to have led his army from Carthage, an ancient city in North Africa, across the southern Alps in 218 BCE. This army, historians say, included 37 elephants.

In his role as general, Hannibal led the Carthaginians’ battle against the Roman Republic in the three Punic Wars, which spanned 264-146 BCE. Archaeologists suspect the site where they found the elephant bone, Colina de los Quemados, may have once been a Punic battlefield.

“Archaeologically, the destruction level documented at Colina de los Quemados fits well within an emerging pattern of events associated with the Second Punic War,” the researchers report.

Artillery projectiles, coins, and ceramics found during excavations in 2020 added further evidence of the site’s military history.

As for the elephant bone, radiocarbon dating confirmed it came from an animal who lived between the late 4th and early 3rd century BCE, right around the time of the Second Punic War.

By comparing the 10-centimeter (4-inch) carpal bone with those of modern elephants and also steppe mammoths, the researchers confirmed it belonged to an elephant. However, it was too degraded for species-level identification, which would require preserved collagen containing protein or DNA.

There are a few other possibilities for how this elephant left a knuckle behind in such an unlikely place. Rome’s Numidian allies may have sent African elephants during the 2nd century BCE as part of conquest campaigns or during Caesar’s civil wars. Or perhaps they were part of gladiator games during the early Roman Imperial period.

Related: Horror of Life on Roman Frontier Revealed in Gut-Wrenching Study

However, these three options don’t quite match up to the bone’s age.

“The Second Punic War context associated with this modest anatomical portion grants the find an exceptional importance, stressing the site’s relevance in future archaeological studies,” the team concludes.

“While [the bone] would not represent one of the mythical specimens Hannibal took across the Alps, it could potentially embody the first known relic − so sought after by European scholars of the Modern Age − of the animals used in the Punic Roman wars for the control of the Mediterranean.”

The research was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.