Just like last year, I watched the most important American speech at the Munich Security Conference in the overflow room, sitting on the floor, underneath the speakers. This is the best place both to hear the speech (otherwise the room is too noisy) and to watch the faces of people gathered around the screens. The prime ministers and presidents sit in the main hall, but plenty of other people attend the conference: security analysts, lieutenant colonels, drone engineers, deputy defense ministers, legislators, and hundreds of other people whose professional lives are dedicated to ending the war in Ukraine, bringing peace to Europe, and projecting security in the world.

Just like last year, this group was hoping to hear how the U.S. administration is planning to contribute to these projects. And, just like last year, audience members were disappointed.

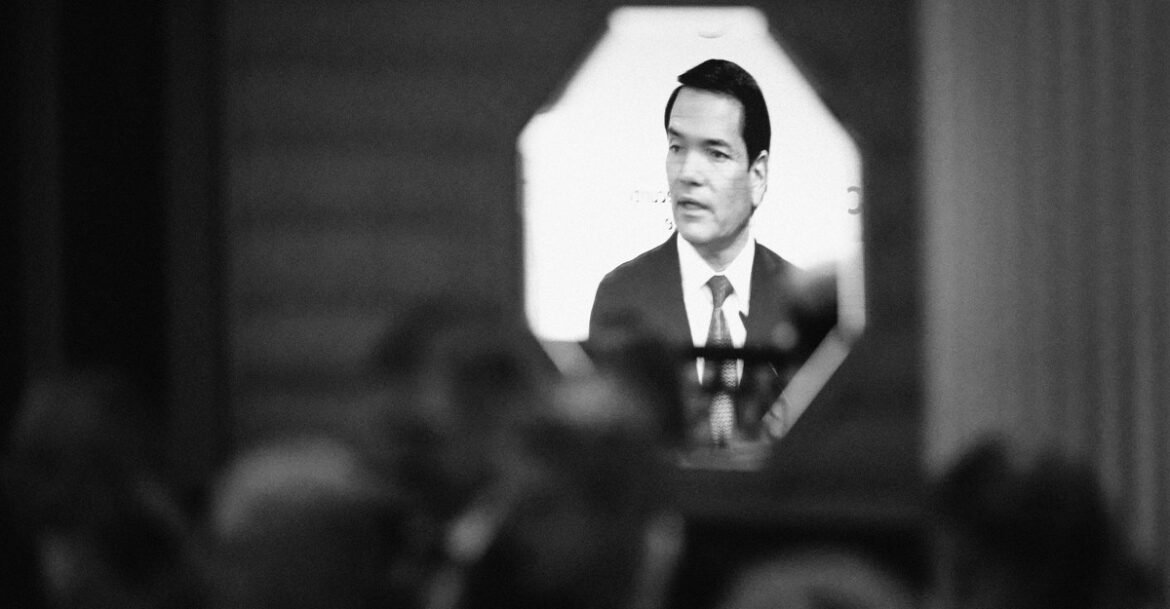

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Saturday’s key speaker, was more civil than Vice President J. D. Vance, who in 2025 attacked and insulted many of the European governments represented in the room. But Rubio’s speech had many of the same goals. He did not mention the war, or imply that America would help Europe win it. He did not express the belief that Russia can be defeated. He did not refer to the democratic values and the shared belief in freedom that once motivated the NATO alliance, and that still motivate its European members. Instead, he offered a vision of unity based on a misty idea of inherited “Western civilization”—Dante, Shakespeare, the Sistine Chapel, the Beatles—which would fight against the real enemies: not Russia, not China, but rather migration, the “climate cult,” and other forms of modern degeneracy.

The speech worked like a Rorschach test. If you wanted to hear some positive news, you might have been satisfied by the emotive expressions of unity. But one of my German friends clearly heard a “dog whistle” to the German far right. I spoke with a couple of Poles who noticed that the list of great men and great artworks failed to include anyone or anything from their half of the European continent. An Indian colleague was alarmed by the praise for colonialism. In Rubio’s repeated references to Christianity, a lot of Americans heard a shout-out to Christian nationalists. And many, many people noticed the oddity of the attack on migration, coming from a son of migrants.

In the hours and days afterward, I did not meet a single person of any nationality who thinks that the American-European relationship is returning to business as usual. Rubio did not say that, and obviously did not want anyone to believe it. Neither did Elbridge Colby, the U.S. undersecretary of defense for policy, who also appeared in Munich. Colby, speaking at a public event, instead promoted the emergence of a “Europeanized NATO” that can defend itself, by itself, with America perhaps offering a theoretical nuclear umbrella. He dismissed the “cloud-castle abstraction of the rules-based international order.” He said that no one should “base alliances on sentiment alone.” This is the message that the Trump administration has been sending all year, and it has not changed.

That message comes with some profound contradictions. Just after Munich, Rubio flew to Bratislava and Budapest, where he heaped praise upon Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian prime minister. President Trump, he told Orbán, is “deeply committed to your success,” a clear reference to upcoming Hungarian elections that Orbán is on course to lose, if the vote is conducted fairly. Many have noted that Orbán has a record of corruption and electoral manipulation, that he puts pressure on judges and independent journalists (hardly any of the latter are left in Hungary), and that Rubio himself signed a letter denouncing the Hungarian prime minister for “democratic erosion” back in 2019.

But in the light of the American message delivered in Munich, the visit was also inconsistent. Orbán, like the far-right leaders in Germany and France who have close ties to Vance and the MAGA establishment, opposes European rearmament. Orbán is not merely seeking to block the emergence of a “Europeanized NATO”; he operates as a de facto spokesman for Russia inside the European Union.

In practice, Orban’s Hungary creates a major security headache for everybody else. Russians are waging a horrific, damaging, costly war on Ukraine. They have sent drones into Europe, staged regular cyber attacks, and cut undersea cables in the Baltic Sea. Does the United States really want Europe to unite and fight these threats together? If so, why is the Trump administration supporting someone who opposes this project? Europeans can’t help but wonder if the American goal is rather to encourage a divided Europe that can’t defend itself against anyone.

Plenty of people heard the open messages and the subtle ones, with some unexpected results. Yesterday morning, Politico’s Brussels Playbook newsletter reported that finance ministers from six European states were meeting in Brussels to discuss the integration of the continent’s financial systems into a capital-markets union. The goal is to jump-start the economy. But as a German friend of mine likes to say, nobody likes capital, nobody likes markets, and nobody likes unions, which is one of the reasons why this long-discussed idea has never created much popular enthusiasm. Some smaller financial institutions might lose out, and they have never been shy about saying so either.

The Trump administration has changed the nature of this discussion. If Europe is to emancipate itself from the United States, and if Europe is to be prepared to defeat Russia, then European defense and technology companies need to grow much faster and raise much more money than they can right now. Instead of investing in America, Europeans will have to keep more of their money at home. In Munich I heard a lot of determination to pursue this goal. None of that is business as usual either.