Every day, thousands of people use indoor gun ranges that are designed to limit the hazards of target shooting, including lead exposure and stray bullets. But shooting indoors poses another hazard that has been almost entirely overlooked: Concussive blast waves that can damage the brain.

Evidence has emerged from the U.S. military that firing some military weapons can damage brain cells, and repeated exposure may cause permanent injuries. But there is next to no public information about the strength of the blast waves delivered by civilian firearms, or the potential hazard.

So The New York Times did its own testing, and gathered its own data. Reporters measured the blasts of several popular civilian guns at an indoor range, using the same sensors that the military uses. The data showed that some large-caliber civilian rifles delivered a blast wave that exceeds what the military says is safe for the brain, and firing smaller-caliber guns repeatedly could quickly add up to potentially harmful exposure. The data also showed that indoor shooting ranges designed to make shooting safe inadvertently make blast exposure worse — doubling and sometimes tripling the amplitude of the blast.

The brain is a delicate network of about 100 trillion connections with a consistency close to Jell-O, and how blasts affect that network is still poorly understood. Experts don’t yet know what level of blast can damage the tissue, or whether blasts that are safe in limited numbers can cause harm with repeated exposure.

With so much unknown, many firearms experts and neurologists say the safest course of action is to limit exposure as much as possible.

The data shows that shooting indoors does the opposite.

Indoor Ranges Exacerbate Blast Waves

There are thousands of indoor ranges in the United States, and many have a similar layout: A row of lanes separated by bullet-resistant walls. Soft, shock-absorbent paneling is not standard and without it the booth can act like an echo chamber, reflecting more of the blast waves back toward the shooter.

The potential for harm from blast waves gets almost no attention from the shooting public, even though people can experience concussion-like symptoms after a day at the range, said Jeff Balcourt, who is an acoustic consultant for the National Shooting Sports Foundation and a designer of indoor ranges for Balco Defense Company.

“It’s one of those unspoken things,” he said. “You don’t realize that after a whole day of shooting, you have that ringing in your ears and that headache.”

Each blast creates waves of rapidly changing high and low pressure. The power of the blast is typically measured by recording the peak pressure of the biggest wave.

The U.S. military currently says that any blast wave that peaks below 4 P.S.I. is safe — though that guideline is not based on solid evidence, and will likely change as research progresses.

In The Times tests, sensors showed that the booth walls doubled the peak pressure for many guns, compared with shooting in the open. With a .357 revolver, the peak pressure tripled.

The smaller-caliber weapons that The Times tested at an indoor range created blasts that measured 1.3 P.S.I. on average — far below the military’s 4 p.s.i safety threshold.

But one gun far exceeded what the military says is safe. A .50-caliber rifle — one of the more powerful guns on the market, which shoots a thumb-sized high-velocity projectile originally designed to pierce vehicle armor — measured 7.6 P.S.I. on average when fired from a prone position.

The rifle’s supersonic blast wave hits the shooter’s head in a fraction of the time that it takes to blink, but using a high-speed camera The Times was able to capture it.

Science has yet to determine how big a blast has to be before it damages brain cells, or whether repeated small exposures may cause microscopic damage to pile up unnoticed over time.

Gary Kamimori, a longtime Army blast safety researcher who retired recently, said that repeated small exposures may cause damage that accumulates unnoticed. He compared the stress put on neurons to what happens to a well-used rubber band.

“Stretch a rubber band a hundred times and it bounces back, but there are micro tears forming,” he said. “The hundred-and-first time, it breaks.”

How High Is Too High?

The potential for harm from blasts is so poorly understood that even the U.S. military’s official safety threshold — 4 P.S.I. — is not based on real evidence. It’s only a place-holder, borrowed from decades-old guidelines for eardrum injuries. The military uses it because it doesn’t have the data yet to arrive at an evidence-based number for the brain.

The actual threshold for brain tissue damage may be much lower than 4 P.S.I. The Canadian military’s recommended safety threshold is 3 P.S.I. A U.S. Army study found symptoms of brain injury in grenade range instructors who were exposed to hundreds of blasts that measured less than 1 P.S.I..

It’s not clear how low the injury threshold might go. It’s not even clear that measuring peak pressure is the best way to gauge the risk.

The current military safety guideline looks only at a blast wave’s highest overpressure peak. But blast waves have dozens of peaks that can pulse through the brain in a few milliseconds.

Blast wave for a single shot from a .50 caliber rifle

Increasingly, Army researchers believe that it may be just as important to calculate the total area of all those peaks — a measurement known as “positive impulse” — and then add up those measurements for every blast a person is exposed to in a day.

Blast wave for a single shot from an AR-15 rifle, 5.56 mm

In recent studies, the Army found that soldiers who were repeatedly exposed over a day of training to a number of blasts that measured around 4 P.S.I. were likely to show signs of slowed cognitive functioning — a possible indicator of brain injury — if the cumulative positive impulse of those blasts added up to 31.7 P.S.I.·milliseconds or more. In other words, multiple blasts within safe levels appeared to add up to an overall exposure that was not safe.

Based on the findings, the military is now considering whether to use a cumulative positive impulse exposure of 31.7 P.S.I.·milliseconds as part of a new daily safety limit. The potential new approach marks a stark change in how the military thinks about the hazard of blast waves. It is being reported here for the first time.

The Times measured an AR-15 rifle against that limit and found that while the peak overpressure of one shot was just 1.6 P.S.I., it took only 20 shots at an indoor range to exceed the proposed daily threshold for cumulative positive impulse. And it can happen fast.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that repeatedly firing an AR-15 rifle will cause a brain injury. But a lot is still unknown.

One of the Army’s lead blast exposure researchers, Walter Carr, said the military had largely focused on the short-term effects of large military weapons, such as artillery, and there had been almost no research on smaller-caliber guns like the AR-15.

A single AR-15 blast might be too small to cause damage, he said. But he cautioned that researchers have not answered that question, and still know little about the cumulative effects of months or years of firing rifles. In the absence of definitive data, he said, many people in the military are informally taking precautions to limit blast exposure whenever possible.

“We didn’t evolve with explosives surrounding us for a period of years,” Mr. Carr said. “It’s a very non-natural type of an exposure. It seems reasonable that there should be consequences.”

How to Reduce Exposure

Discussions in online shooting forums show that shooting enthusiasts regularly mention concussion-like symptoms, but talk about the risk of brain injury is rare. Post-shooting symptoms like headaches, fatigue and brain fog, which may be related to a brain injury, are often attributed instead to noise, tight-fitting protective gear, dehydration or poor ventilation.

One person may feel fine after shooting, and another may feel concussed, because not everyone is affected in the same way. Age, fitness level, prior history of contact sports, pre-existing brain injuries and other factors may all make some people more vulnerable than others.

Bottom line: Many neurologists say that if you are feeling ill effects from shooting, limit your exposure.

Blast magnitudes measured by The Times at an indoor gun range

| .50 BMG rifle | 6.7 | |

| .50 AE Desert Eagle | 3.4 | |

| .500 Mag. revolver | 2.9 | |

| .357 Mag. revolver | 1.8 | |

| AR-15, 5.56 mm | 1.6 | |

| 9-mm pistol | 1.3 | |

| Bullpup rifle, 5.56 mm | 1.1 | |

| 12-gauge shotgun | 1.0 | |

| 1911 pistol, .45 ACP | 1.0 |

Fortunately, there are simple ways to limit exposure. The Times found that shooting in an open outdoor setting, rather than in an enclosed booth, can cut blast levels by more than half. When shooting indoors, ensuring that the gun barrel extends beyond the booth can reduce exposure. Choosing smaller caliber weapons and less powerful ammunition can also help.

Attaching a suppressor or blast regulator to the muzzle to direct the blast forward and away from the shooter can also make a big difference. In The Times testing, the blast from firing an AR-15 rifle indoors measured as high as 1.7 P.S.I. When a blast regulator was added, the measurement fell to less than 0.5 P.S.I.

Suppressors and regulators are often used by law enforcement and the military, but they’re pricey, and suppressors are tightly regulated in some states and illegal in others.

Lucas Botkin, who founded the popular firearms parts and accessories company T.Rex Arms and hosts a popular YouTube channel focused on shooting, said the concussive damage from shooting is a big reason muzzle devices like suppressors should be widely used.

“I know I’ve been messed up,” Mr. Botkin said. “And I have a bunch of buddies who are blasted just from shooting small arms for hundreds of thousands of rounds.”

Methodology

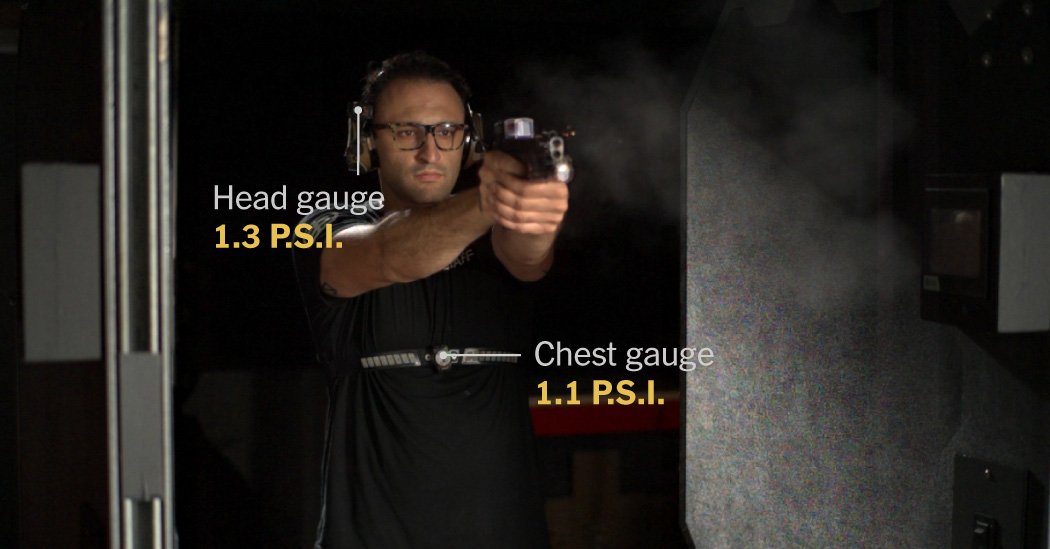

The Times recorded blast overpressure using the BlackBox Biometrics Blast Gauge System, with sensors fastened to the chest and the right side of the head of the shooter, recreating a setup regularly used to record blast exposure in the military. We used only the readings from the head gauge for this report. The readings from the chest gauge were used to check the reliability of the head gauge readings.

The gauges automatically calculate peak positive pressure and positive impulse for each shot. We added up individual positive impulse readings of the head gauge to determine the cumulative positive impulse of multiple shots. The ammunition used for the tests were common training rounds that are often used for target practice. The AR-15 was tested with both 5.56 mm and .223-caliber ammunition; the two types yielded similar blast readings.

For most weapons, averages using the three highest recorded readings are shown. For the Desert Eagle, the average of two readings is shown.