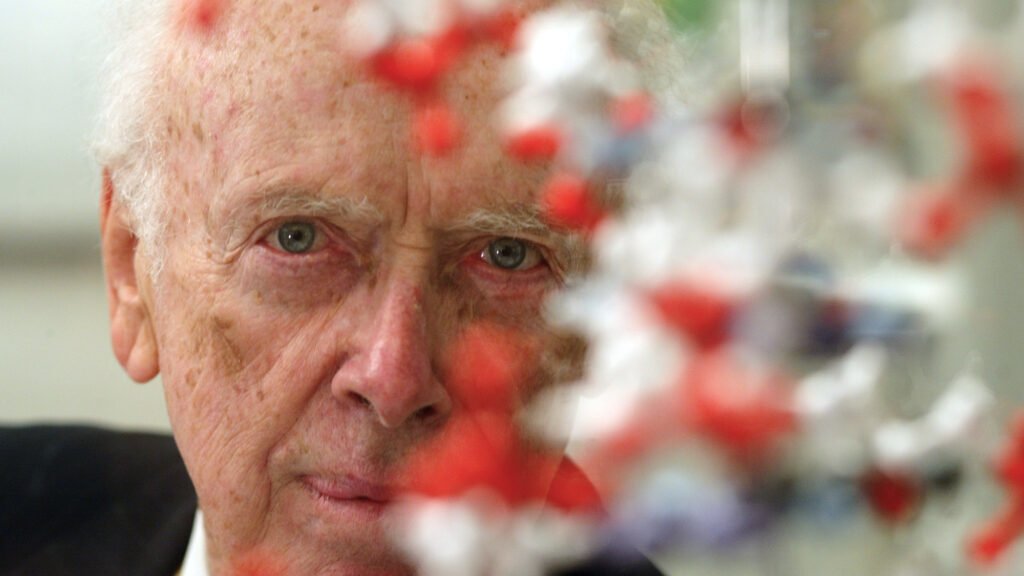

When biologist James Watson died on Thursday at age 97, it brought down the curtain on 20th-century biology the way the deaths of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson on the same day in 1826 (July 4, since the universe apparently likes irony) marked the end of 18th-century America. All three died well into a new century, of course, and all three left behind old comrades-in-arms. Yet just as the deaths of Adams and Jefferson symbolized the passing of an era that changed the world, so Watson’s marks the end of an epoch in biology so momentous it was called “the eighth day of creation.”

Do read some of the many Watson obituaries, which recount his Nobel-winning 1953 discovery, with Francis Crick, that the molecule of heredity, DNA, takes the form of a double helix, a sinuous staircase whose treads come apart to let DNA copy itself — the very foundation of inheritance and even life. They recount, too, Watson’s post-double-helix accomplishments, such as pulling Harvard University’s biology department, with its focus on whole animals (“hunters and trappers,” the professors were called) kicking and screaming into the new molecular era in the 1970s. Watson also transformed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on New York’s Long Island — which he led from 1968 to 2007 — into a biology powerhouse, especially in genetics and cancer research. And starting in 1990 he served as first director of the Human Genome Project, giving his blessing to an effort that many biologists viewed with disdain (a Washington power struggle forced him out in 1992).

What follows is more like the B side of that record. It is based on interviews with people who knew Watson for decades, on Cold Spring Harbor’s oral history, and on Watson’s many public statements and writings.

Together, they shed light on the puzzle of Watson’s later years: a public and unrepentant racism and sexism that made him a pariah in life and poisoned his legacy in death.

Watson cared deeply about history’s verdict, which left old friends even more baffled about his statements and behavior. It started in 2007, when Watson told a British newspaper that he was “inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa” because “social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours — whereas all the testing says not really.” Moreover, he continued, although one might wish that all humans had an equal genetic endowment of intelligence, “people who have to deal with Black employees find this not true.”

He had not been misquoted. He had not misspoken. He had made the same claim in his 2007 memoir, “Avoid Boring People: Lessons from a Life in Science”: “There is no firm reason to anticipate that the intellectual capacities of peoples geographically separated in their evolution should prove to have evolved identically,” Watson wrote. “Our wanting to reserve equal powers of reason as some universal heritage of humanity will not be enough to make it so.” As for women, he wrote: “Anyone sincerely interested in understanding the imbalance in the representation of men and women in science must reasonably be prepared at least to consider the extent to which nature may figure, even with the clear evidence that nurture is strongly implicated.”

There was more like that, and worse, in private conversations, friends said. Watson became an untouchable, with museums, universities, and others canceling speaking invitations and CSHL giving him the boot. (Though as memories of his worst remarks receded, Watson enjoyed sporadic rehabilitation.) Friends were left shaking their heads.

“I really don’t know what happened to Jim,” said biologist Nancy Hopkins of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who in the 1990s led the campaign to get MIT to recognize its discrimination against women faculty. “At a time when almost no men supported women, he insisted I get a Ph.D. and made it possible for me to do so,” she told STAT in 2018. But after 40 years of friendship, Watson turned on her after she blasted the claim by then-Harvard University president Lawrence Summers in 2005 that innate, biological factors kept women from reaching the pinnacle of science.

“He demanded I apologize to Summers,” Hopkins said of Watson. (She declined.) “Jim now holds the view that women can’t be great at anything,” and certainly not science. “He has adopted these outrageous positions as a new badge of honor, [embracing] political incorrectness.”

A partial answer to “what happened to Jim?”, she and other friends said, lies in the very triumphs that made Watson, in Hopkins’ words, unrivaled for “creativity, vision, and brilliance.” His signal achievements, and the way he accomplished them, inflated his belief not only in his genius but also in how to succeed: by listening to his intuition, by opposing the establishment consensus, and by barely glancing at the edifice of facts on which a scientific field is built.

One formative influence was Watson’s making his one and only important scientific discovery when he was only 25. His next act flopped. Although “Watson’s [Harvard] lab was clearly the most exciting place in the world in molecular biology,” geneticist Richard Burgess, one of Watson’s graduate students, told the oral history, he discovered nothing afterward, even as colleagues were cracking the genetic code or deciphering how DNA is translated into the molecules that make cells (and life) work.

“He fell flat on his nose on all these problems,” Harvard’s Ernst Mayr (1904-2005), the eminent evolutionary biologist, told the oral history. “So except for this luck he had with the double helix, he was a total failure!” (Mayr acknowledged the exaggeration.) By the 1990s, even Watson’s accomplishments at Harvard and CSHL were ancient history.

Watson nevertheless viewed himself “as the greatest scientist since Newton or Darwin,” a longtime colleague at CSHL told STAT in 2018.

To remain on the stage and keep receiving what he viewed as his due, he therefore needed a new act. In the 1990s, Watson became smitten with “The Bell Curve,” the 1994 book that argued for a genetics-based theory of intelligence (with African Americans having less of it) and spoke often with its co-author, conservative political scholar Charles Murray. The man who co-discovered the double helix, perhaps not surprisingly, regarded DNA as the ultimate puppet master, immeasurably more powerful than the social and other forces that lesser (much lesser) scientists studied. Then his hubris painted him into a corner.

Although the book’s central thesis has been largely discredited, Watson embraced its arguments and repeated them to anyone who would listen. When friends urged him to at least acknowledge that the book’s science was shaky (or worse), Watson wouldn’t hear of it.

“He loved getting a rise out of people,” the lab friend said. “And when you think of yourself as a master of the universe, you think you can, or should, get away with things.”

When the friend proposed that Watson debate the genes/IQ/race hypothesis with a leading scientist in that field, for a documentary, Watson wouldn’t hear of it: “No, he’s not good enough” to be in the same camera frame as me, Watson replied, the friend recalled. “He saw himself as smarter than anyone who ever actually studied this” — which Watson had not.

Friends traced Watson’s smartest-guy-in-the-room attitude, and his disdain for experts, to 1953. When he joined Crick at England’s Cavendish laboratory, Watson knew virtually nothing about molecular structures or “the basic fundamentals of the field,” Jerry Adams, also one of Watson’s graduate students, told the oral history; Watson was “self-taught.” He saw his double-helix discovery as proof that outsiders, unburdened by establishment thinking, could see and achieve what insiders couldn’t.

That belief became cemented with his success remaking Harvard biology. The legendary biologist E.O. Wilson, who was on the losing end of Watson’s putsch, called him “the most unpleasant human being I had ever met,” one who treated eminent professors “with a revolutionary’s fervent disrespect. … Watson radiated contempt in all directions.” But in a lesson Watson apparently over-learned, “his bad manners were tolerated because of the greatness of the discovery he had made.”

Watson saw his slash-and-burn approach at Harvard as proof that disdaining the establishment pays off.

Perhaps in reaction to Watson’s sky-high self-regard, in his later years his peers and others began to ask if his discovery of the double helix was just a matter of luck. After all, as a second lab colleague said, “Jim has been gliding on that one day in 1953 for 70 years.”

With Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray images (which Watson surreptitiously studied), other scientists might have cracked the mystery; after all, American chemist Linus Pauling was on the DNA trail. But Watson had something as important as raw skill and genius: “He realized that to discover the structure of DNA at that moment of history was the most important thing in biology,” Mayr told the oral history. Although Crick kept veering off into other projects, he said, “Watson was always the one who brought him back and said, ‘By god, we’ve got to work on this DNA; that’s the important thing!’” Knowing the “one important thing” to pursue, Mayr said, “was Watson’s greatness.”

That was only the most successful result of following his instinct; whether getting the Human Genome Project off the ground or running CSHL, Watson was a strong believer in finding truths in his gut. “Jim is intuitive,” MIT biologist H. Robert Horvitz told the oral history. “He had an uncanny sense of science and science problems.”

He came to believe in his intuition about something else: race and IQ and genetics. His gut, he felt, was a stronger guide to truth than empirical research or logic. As a result, “he believed what he believed and wasn’t going to change his view,” the lab friend said. “It’s not as simple as courting controversy for controversy’s sake. But as the scientific environment became even less hospitable to [the “Bell Curve” thesis], he became even more adamant. He loved trashing the establishment, whatever it is.”

Watson’s loss of his CSHL position, the rescinded invitations, the pariah status, also had their effect. The setbacks made him “resentful and angry,” the lab friend said. “‘Saying the right thing’ now translated into ‘political correctness’ in his mind. And that made him say even more outrageous things.”

Over the two years that filmmaker Mark Mannucci spent with Watson for an “American Masters” episode that aired on PBS in 2019, Watson “continued to spew toxic material,” the friend said. Asked on the show whether his views about race and intelligence had changed, he replied, “Not at all. I would like for them to have changed, that there be new knowledge that says that your nurture is much more important than nature. But I haven’t seen any knowledge.” Within days, Cold Spring Harbor severed all remaining ties with Watson, citing his “unsubstantiated and reckless” remarks.

Those statements seemed to be a way to lash out at the establishment that had shunned him since 2007 and to retain a few photons of the public spotlight. “In the old days, Jim actually had power and could satisfy himself by getting things done the way he saw fit,” said the lab friend. “The current Jim has no power.” Added Hopkins, “He built the field of modern biology, but he didn’t know when to get off the stage.”

At age 90, Watson told friends he did care how history would see him. He did care what his obituaries would say. He knew his racist and sexist assertions would feature in them. Not even that could make him reconsider his beliefs, which only seemed to harden with criticism. Now history can reach its verdict.