I’m not being facetious when I say that I remember exactly where I was when I first became aware of Anthony Bourdain. It was the summer of 2002, two years after he published “Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly,” a seminal and unsparing account of life as a chef in restaurant kitchens. I was fifteen, and on vacation with a friend and her family, on Long Island. My friend’s father was reading the paperback and shared aloud one of the dirty secrets in the book, which we all took, immediately, as gospel: one should never order fish on a Monday.

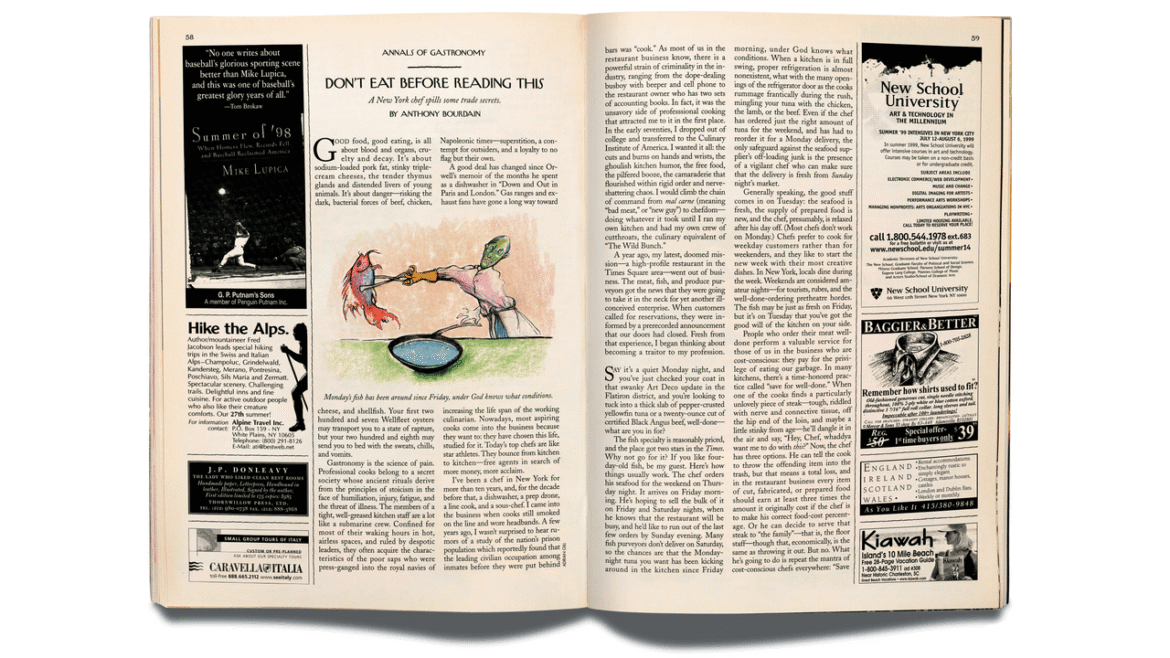

Bourdain’s elaborate passage explaining why this was true had first been published, in The New Yorker, in the 1999 essay “Don’t Eat Before Reading This,” which he expanded, rapidly, into “Kitchen Confidential.” (The short answer was that “many fish purveyors don’t deliver on Saturday, so the chances are that the Monday-night tuna you want has been kicking around in the kitchen since Friday morning, under God knows what conditions”; the long answer took you deep into the culture and psychology of the restaurant business.) He wrote it, originally, for an alt-weekly called the New York Press, which had slated it as a cover story before the editor killed it at the last minute. Bourdain had imagined his audience would be insular and small: “I thought, I’m going to write something that will entertain other cooks, maybe I’ll get a hundred bucks, and my fry cook will find this funny,” he recalled in 2017, during an appearance at The New Yorker Festival. When the article found its way into The New Yorker—after Bourdain’s mother suggested to a New York Times colleague, Esther Fein, that Fein’s husband, David Remnick, the magazine’s new editor, might want to take a look—“it transformed my life within two days,” he said.

You could explain the splash by pointing to the essay’s tell-all nature, the invitation it offered into a thrillingly seedy world that had been right under everyone’s nose. The chefs cooking your meal are not wearing gloves or hairnets; the waitstaff is recycling the remnants of your bread basket; on average, you’re consuming probably a stick of butter per restaurant meal: “sauces are enriched with mellowing, emulsifying butter. Pastas are tightened with it. Meat and fish are seared with a mixture of butter and oil. Shallots and chicken are caramelized with butter. It’s the first and last thing in almost every pan: the final hit is called ‘monter au beurre.’ ” But Bourdain was much more than a whistle-blower, even at the very beginning of what would become his second, highly significant career. The aw-shucks way he sometimes told the story of writing the essay and getting it published belied the years he had spent pursuing his literary ambitions, even while working the line and maintaining a heroin addiction; in 1985, he took a workshop with the renowned editor Gordon Lish, and before he made it into The New Yorker he had published two novels, including a crime thriller, and was sitting on a novella based on his kitchen experiences.

The voice he introduced in “Don’t Eat Before Reading This” is not just brash and ballsy; it reverberates with style and poetry, from its tantalizing opening lines: “Good food, good eating, is all about blood and organs, cruelty and decay. It’s about sodium-loaded pork fat, stinky triple-cream cheeses, the tender thymus glands and distended livers of young animals. It’s about danger—risking the dark, bacterial forces of beef, chicken, cheese, and shellfish.” Though it was Bourdain’s documentary television shows that made him extraordinarily famous—the sort of celebrity whose face ends up on novelty votive candles and tattooed onto people’s biceps, who persuades a sitting President to eat grilled pork and noodles and drink beer on a plastic stool in Vietnam—“Kitchen Confidential” has become canonical, and everything he did was writerly, vividly observed, and incisively interrogated.

As Bourdain himself pointed out, before his death by suicide, in 2018, the no-fish-on-Monday rule expired many years ago, thanks to improvements to the supply chain. What will far outlast him is his example, his uncommon ability to show thorny things exactly as they were without ever making them seem ugly. ♦