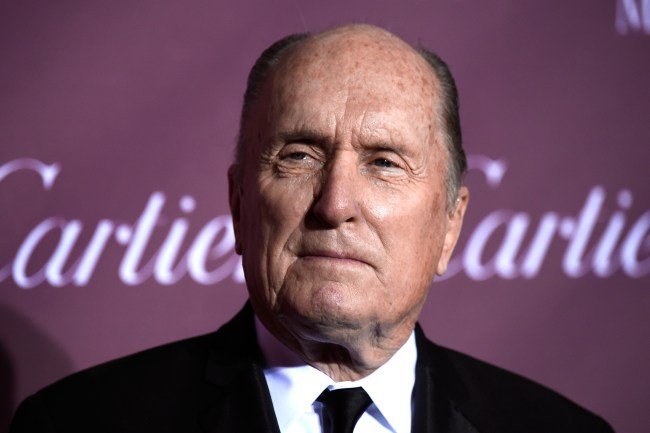

Robert Duvall, the Oscar-winning actor and New Hollywood legend, has died at the age of 95. The news was shared by his widow, Luciana Duvall.

“Being an actor,” Duvall said near the end of his career, “You live an imaginary existence between ‘action’ and ‘cut’. When you live between those two words, you try to create something that’s from yourself, that’s alive, and legitimate and truthful.”

Any tally of the great film and small screen actors of our era undeniably includes him in the front rank (Vincent Canby called him, at a mid-career point, America’s Olivier), and he worked with some of the best of that elite group. Not only convincingly naturalistic onscreen, he bore a humility that made him perhaps the least self-mythologizing of the lot. His lack of pretension, reflected in performances that found power in subtlety, only added to the admiration of his peers and the public.

Consider his take on shooting the first two films of the “Godfather” trilogy with Frances Ford Coppola—alongside Marlon Brando, with James Caan, Al Pacino and John Cazale as his brothers: “We didn’t talk a lot about this and that, this and that — we just kind of went ahead with our natural impulses.”

Directors, including those whose patience had been tested by his uncompromising work process, found that he rarely theorized about his actual craftsmanship even with his workmates. Over time, he nonetheless gave engaging interviews to the press, most notably to The Washington Post — as one mainly raised in Maryland and settled in Virginia, it was his hometown paper — that allowed some insight into how he utilized his sheer talent. In one, he described his long-recalled memory of shooting the scene in “The Godfather” (1973) where his character, Tom Hagen, tells Brando’s Don Vito that James Caan’s Sonny has been killed. Duvall as Hagen has poured a drink before the revelation, but Brando joins him with an awareness of trouble, and the news is given and received with implacable dignity by both. A masculine restraint marks their half-hug — Duvall still seated, Brando drawing him in like the child he had been when the family (in fact, Sonny himself) brought him home off the streets. Brando as don and Duvall as consigliere perfected the scene in two takes. Asked by Coppola if they wanted another, they, as one, refused. Well aware of the pair’s shared credo that film acting at its best replicates the immediacy of stage work, the director moved on.

Duvall would maintain he knew they were making a classic. Even the readily ignited Pacino as mob scion Michael was turning in his most reined-in, murmurous performance — only to be out-underplayed by Duvall at points. In 1974’s “Godfather II,” which served as both prequel and sequel to the earlier film, internecine mob warfare is coming as Michael tells his adoptive brother he’s needed to serve as acting don and protector of Michael’s family. Exuding characteristic emotional steadiness, Tom waits a beat before allowing himself to say he always wanted to be thought of as a true brother. And yet they would arrive at an equally striking moment when Tom is shifted (strategically, though he doesn’t yet know that) to a sideline role: “Why do you hurt me, Michael? I’ve always been loyal to you.”

Duvall would assess that Coppola’s genius in making the film that started with only weak studio support was to bear down on the family’s depths and let the rich story play out slightly in the background. And indeed, the first of the Mafia epic brought Duvall his first Oscar nom for as a Supporting Actor even as Brando was named Best Actor; Pacino and Caan also were nominated as best supporting actors. (Pacino didn’t attend, charging that his nom should have been as Best Actor — which is perhaps how dark horse Joel Grey picked up the supporting actor statuette to the gleeful strains of “Cabaret.”)

Duvall had been cast thanks to his work in Coppola’s 1969 “The Rain People,” with his pal since early scuffling days, Caan, saying of a fired actor’s role, “Duvall could play that part.” He’d be paid equitably for both “Godfather” films, but when they offered him a salary less than half of Pacino’s take for the third iteration, it may have been more a matter of pride than finances that caused him to decline the job.

It takes nothing away from Duvall’s track record to say he had the good fortune to arrive as character actor with a leading man’s magnetism even as film was embarking on what now feels increasingly like a golden era. He made the stars working beside him better — “The Number 1 Number 2,” as TIME magazine put it.

Coppola memorably redeployed him as the surfer-enthusiast bringer of war Col. Kilgore in 1979’s ”Apocalypse Now.” Duvall signed on only after scaling the character from “A cowboy in boots” named Col. Carnage into a charismatic Air Cavalry officer who unforgettably loved “the smell of napalm in the morning.” By 1981 in “The Great Santini”, he was marine aviator Bull Meechum, pestiferously bouncing a basketball off his son’s head to snag a Best Actor Oscar nom — which tee’d him up for his Best Actor Oscar win as a faded, alcoholic country singer in 1983’s “Tender Mercies.” It would be over a decade of continuing fine work before nominations began to reappear — as Best Actor in 1997’s “The Apostle”, as Best Supporting Actor for 1998’s “A Civil Action,” and in 2014, another supporting nom as the crabby, conflicted title character opposite Robert Downey, Jr. in “The Judge.”

Duvall’s television career has its own unique arc, beginning in roles like a gun-wielding thug on a rooftop in “Naked City,” and as the ineffectual clerk who falls for a miniature come-to-life beauty from a museum dollhouse in Twilight Zone’s “Miniature,” to the ultimate small screen mini-series that stood high in its category, the 1989 eight-hour adaptation of Larry McMurtry’s popular and Pulitzer-winning Old West fiction classic ”Lonesome Dove.” As a salty, retired Texas Ranger impelled into a savagely testing late 19th-century cattle drive from the Rio Grande to Montana, Duvall elevates McMurtry’s eloquence, via Bill Wittliff’s teleplay, into classic fare. On the advice of his then-wife, Gail Youngs, he had insisted on playing Gus McCrae, handing off the original proffer of playing fellow ex-Ranger Woodrow to Tommy Lee Jones.

He would sum up the experience this way: “I was fortunate to be in the two big film epics of the last part of the 20th century: ‘Godfather’ and ‘Lonesome Dove’ on television, which was my favorite part. That’s my “Hamlet. The English have Shakespeare; the French, Molière. In Argentina, they have Borges, but the Western is ours. I like that.”

Robert Duvall was born January 5, 1931, in San Diego, California, as the second of three sons to Mildred Virginia Duvall, an aspiring actress, and Virginia-born Navy Rear Admiral William Howard Duvall. Raised as a believer in the Christian Science religion but seldom a church attendee, he was schooled in Maryland and graduated with a B.A. in 1953 from Principia College in Illinois. The Navy brat joined the Army in 1953, emerged as a Private First Class, and hit New York in the winter of 1955 to begin studying at Neighborhood Playhouse under Sanford Meisner. When 21-year-old Dustin Hoffman arrived in Manhattan in 1958, he sought out his fellow alum of the Pasadena Playhouse College of Theatre Arts, Gene Hackman, who made the connection to Meisner classmate Duvall. “The three,” the New Yorker would write, “were instantly inseparable. Half a century on, they can count five Oscars among them, but back then, nobody knew who they were, including themselves.”

The answers showed up quite quickly, in professional life at least. Horton Foote was already a playwright of note, and working with the Neighborhood Theater, when he was advised to see the student production of his 1957 play, “The Midnight Caller.” Struck by Duvall’s authenticity as an indigent alcoholic, he asked where the actor’s behavior had come from. A colleague told him that the actor didn’t drink or smoke but had spent ample time on the Bowery watching the ways of what were then called “bums”.

“God gave him certain attributes,” Foote would say, “He was born with an extraordinary ear. He can pick out– with imitating– the specifics of an accent and the characteristics of a character. His sense of hearing, his sense of observation are extremely acute.”

When Foote’s ”To Kill A Mockingbird,” was mounted in 1962, the brief but crucial part of mysterious recluse Boo Radley went to Duvall. That outing epitomized what film critic David Thomson deduced: “His early parts were in a vein of troubled loneliness that testifies to the starring severity of his face.” Thomson further postulated that, much as he had been as he would be in the Godfather world, “Duvall the actor relates to high stardom like an Irishman among Italians… on occasions his prominent forehead and his possessed gaze have conveyed an anguish or obsession that might be more worthwhile than moody glamour.”

As Duvall’s stature grew, he was sufficiently in demand to enforce certain prerogatives of a star. He scrapped with director Henry Hathaway on “True Grit” (1969) even as he left star John Wayne the space to carry the hero story, what Thomson saw as Duvall’s “tidying up around [stars’] grand gestures.” He blocked his on-camera moves according to his own logic, obeying only his sense of what was authentic to actual human behavior. The Washington Post described his foil to Wayne, Ned Pepper, as “always laughing that dark, choked Duvall laugh.” When asked about a history of on-set quarrels and their cause, he mused unapologetically: “Vibes. Power…I get irritable on the set…sometimes you, like snap, but it comes out of the moment, and you apologize.”

His range was his hole card. A role in 1970’s “M*A*S*H was less minimal than had been his norm, but he found the truth in playing martinet Major Frank Burns as straightforwardly creepy—steering clear of signaling to the audience that he, as an actor, knew what kind of villain he was playing.

Rising directors sought him out from early on — George Lucas for “THX 1138” in 1971, Clint Eastwood for “Joe Kidd” the following year, and he was unafraid to repay Foote by taking on a role in what would be a favorite, 1972’s “Tomorrow,” an adaptation of a Faulkner story about poor Mississippians — “the lowly and invincible of the earth.”

From the ascendancy as a Coppola go-to, including “The Conversation” in 1974 and “Apocalypse Now” in 1979, Duvall relentlessly stayed busy — his film tally hovers near a hundred outings — and in a way he never ceased arriving as the virtuous, if not always epochal projects arrived apace: “True Confessions” (1981), “The Natural” (1984), “Days of Thunder” (1990), “Rambling Rose” (1991), “Falling Down” (1993), “The Paper” (1994), “Sling Blade” (1996), “Gone in 60 Seconds” (2000), “Open Range” (2003) “Crazy Heart” (2009), “Get Low” (2010), “Jack Reacher” (2012), and Widows (2018).

Amidst that skein, perhaps no film was closer to his artistic heart than 1998’s “The Apostle,” made at age 66, after he’d spent 13 years and $5 million of his own money: “I studied preachers all over America…we make great gangster movies. So why not make this kind of movie right, too? He got a letter from Brando, an “acceptance” of the job he framed on his wall: “I like it more than my Oscar.”

Having been dubbed a documentary-style actor, he at intervals made his own documentaries, because, he said, “I learn so much about acting.” Thus came his films about a Nebraskan rodeo clan, “We’re Not the Jet Set” (1974), and Romani families in New York (“Angelo, My Love,” 1983). In a turn towards drama that could incorporate his love of a Latin American dance form, he directed 2003’s “Assassination Tango.” He was 84 in 2015 when he made “Wild Horses,” the story of a Texan rancher facing his last years.

Always underrated, he felt, was his portrayal of the revolutionary and eventually Soviet autocrat of “Stalin” (1992), which earned him a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Television Film.. He strove to find the tyrant’s “vulnerability” using a bit of a crush on co-star Julia Ormond: “The girl that played his second wife, the one that committed suicide, I kind of had an infatuation for her. He must have had some kind of feeling toward her after that, so that’s what worked on me.”

He had the license in the trade to become a sacred monster (Brando would have been a handy example), but he remained an honest worker. The likes of Tom Cruise, Kevin Costner, Jeff Bridges, and Bill Murray all wanted a crack at working alongside the veteran ace. As late as 1998’s “A Civil Action,” written and directed by Steven Zallian with John Travolta as co-star, won Duvall a SAG Award for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role.

A late-innings effort dear to his artistic precepts came with 2013’s Spanish-American Western, “A Night in Old Mexico,” reuniting him with screenwriter Wittliff. The New York Times found much to like in “none too cuddly” unveiling of an aging crank: “When he has fun, he lets us in on it.”

If it was a sort of recall of his sometime favorite role, as his rowdy, doomed, smack-talking Gus McCrea in “Lonesome Dove” (a jocund yakker he insisted could have been at home in a Shakespeare play), Duvall never let loose of his quest for authenticity. “Someone once told me, ‘Just play the facts,’ ” Duvall said late in his career, “You see so many talented people who go for what they figure their strength is — crying or whatever. But you see a guy who’s lost his kid in the flood, and you don’t see him trying to make points going for tears, like you see certain actors do.”

He never tired of reminding anyone who asked that he was not a method practitioner. “I don’t become the character! It’s still me — doing myself, altered. “

It’s a rigor that locked usefully with another of his proudly repeated rulings that tested the patience of some collaborators: “I do my own horsemanship, my own singing and my own dancing in a movie,” he says. “It’s me that has to do that.”

But his summarizing thought is most vividly illustrated by his career since its earliest days, as he considers an actor’s discipline with gesture. “It doesn’t have to be a grand thing,” he said, with a credibility that made him something of a legend in his trade, “It can be a little thing that just goes, like, pow!”