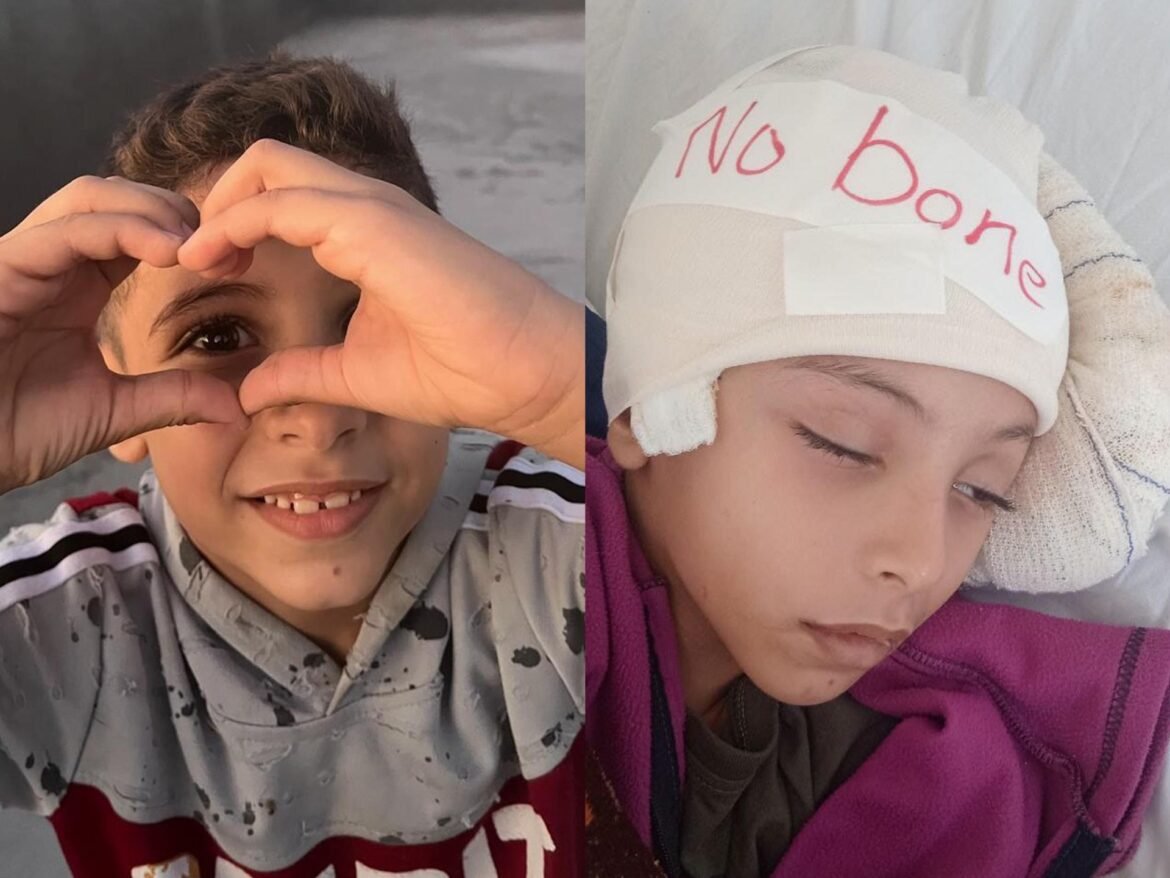

My cousin Ahmad was nine years old when he suffered a severe head injury in Gaza. A year ago, a missile hit the house next to ours in Nuseirat. The explosion was so violent that it pushed Ahmad off the third-floor staircase of our building. He fell badly on his head, shattering his skull.

We carried him to Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital, where the doctors fought for his life. There were moments when the heart monitor barely registered a heartbeat. We all thought we had lost him forever, but Ahmad, with the stubbornness he was known for, challenged death itself.

He survived. Two days later, he was transferred to the European Hospital, where doctors operated to stop the bleeding in his brain and removed roughly one-third of his skull to reduce the pressure. He spent two weeks in the intensive care unit on oxygen and mechanical ventilation. He lost his ability to speak and became paralysed on his left side. His eye nerve was also damaged from the head trauma, and he is at risk of losing his eyesight.

After he regained consciousness, he was kept in the hospital for several more weeks before being transferred to a hospital run by the Red Crescent, where he received physiotherapy for a month and a half. The plan was to stabilise him for several more months before doing a surgery to insert an artificial bone to cover his brain.

But on one of Ahmad’s final days at the hospital, the Israeli army bombed so close to the facility that shrapnel and rubble hit the building. Large debris fell just a few centimetres from Ahmad’s head in the room he was in. That terrified his family and the doctors. They decided it was too dangerous for him to remain without a skull bone in such conditions, so he was transferred back to the European Hospital for surgery.

A synthetic bone was implanted to reconstruct the missing part of Ahmad’s skull. He remained in the hospital for two weeks after the surgery before he was discharged. He was supposed to be on a nutrient-rich diet to recover, but soon famine hit Gaza.

His family couldn’t buy any milk, eggs or any other nutrient-rich foods to help Ahmad heal. Some days, my aunt Iman, Ahmad’s mother, could not even find a kilo of flour. Malnutrition ate away at his recovery. The artificial bone in his skull began collapsing. If one was to gently press the soft area of his head, their fingers would sink in almost 2cm (three-quarters of an inch).

Today, Ahmad lives in a nightmare: a severe head injury, brain bleeding, one eye damaged, half of his body paralysed. He urgently needs reconstructive skull surgery, eye surgery and continuous, intensive physiotherapy.

Despite everything, his mother has tried to keep him integrated so he won’t fall into despair. A few weeks ago, she enrolled him in a tent school so he wouldn’t fall behind his peers. Every day, she would take him there with a notebook and pen. But when they would get back to their tent and take out the notebook, the pages would always be blank.

Eventually, my aunt went to speak to his teachers about this. They told her that he cannot write for more than two minutes before the pain in his head becomes unbearable. He would cry, throw the pen away and lay his head on the table.

His mother tried to teach him at home, but he must sleep one hour before studying and half an hour after, and even then, he struggles to absorb information.

Ahmad is one of 15,600 sick or injured Palestinians who need urgent treatment outside Gaza. Since October 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) has evacuated more than 7,600 patients from the Gaza Strip, two-thirds of them children. But in recent months, those evacuations have slowed to a trickle.

After the latest ceasefire began on October 10, the first medical evacuation took place two weeks later and included just 41 patients and 145 companions.

The Rafah crossing with Egypt remains closed. Israel now allows medical evacuations only through the Karem Abu Salem crossing in small and unpredictable numbers. Israel controls who gets on the list for evacuation and who gets approval to leave. The process is painfully slow. At the current rate, it would take years to evacuate everyone. Many will not make it.

But Israel is not the only barrier. Even when patients get approval, that does not mean they will leave. They still need funding to pay hospital bills and a foreign government willing to grant them visas.

While medical evacuations are recommended by local hospitals, the process itself is managed by the World Health Organization, which is trying to press foreign governments to cover evacuations, but the list is too long, and few countries are willing to accept patients from Gaza. In many urgent cases, families cannot wait so they try to secure funding or contact foreign hospitals themselves.

People wait. Days, months pass. Patients’ conditions worsen. Some pass away waiting.

Ahmad was initially classified as “not a priority” because he had his first surgery. But famine caused his condition to deteriorate. After repeated attempts by local doctors to prove that Ahmad deserved evacuation, he finally got approval. His family felt joy they hadn’t felt in months.

But then came the shock.

They were told they were responsible for securing treatment themselves, and the funding required for Ahmad’s treatment in a hospital abroad was unaffordable for a displaced family living in a tent. His parents – a teacher and a professor – work, but they do not receive regular salaries. They still pay the bank monthly instalments for a mortgage on their home, which was bombed into ruins. Their meagre income barely covers life in a tent.

But they have not given up. Ahmad’s brother, Yousef, is regularly contacting hospitals abroad, trying to find one that would take on his treatment. His father, Hassan, is writing to contacts abroad, hoping to find anyone who can help.

They keep fighting, but Ahmad’s condition is getting worse. He has now started forgetting the names of family members.

So many children like Ahmad are languishing in Gaza, waiting to be evacuated. Israel, as an occupier, bears the main responsibility. But what is the world doing to save these children?

Wealthy governments that funded and supported the genocide have looked away. They either accept a few cases or none at all. Their refusal to act, to acknowledge Palestinian children’s suffering, to accept their humanity is yet another sign of their moral bankruptcy.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.