MUNICH, Germany — For decades, space was imagined as a kind of neutral commons — a quiet layer of infrastructure floating serenely above earthly conflict. At the Munich Cyber Security Conference this week, that idea sounded less like policy and more like nostalgia.

Military officials, regulators and technology executives described an orbital environment that no longer resembles a scientific frontier. Instead, it looks increasingly like the next arena of great power competition — crowded with satellites, vulnerable to disruption, and governed by rules written for a far simpler age.

Modern life depends on those machines overhead in ways that are easy to forget until they fail. GPS timing synchronizes banking networks. Satellites link military forces across continents. Weather data guides aviation and agriculture. Missile-warning systems underpin nuclear deterrence. Disable those systems — even briefly — and the consequences would ripple outward at devastating speed.

“If satellites are your eye on the target, you want your enemy to be blind in a conflict,” one industry executive warned, distilling a strategic logic that has long shaped military planning.

The subsea cable vulnerability

The push toward space is driven, in part, by vulnerability here on Earth: a global network of undersea cables that can be cut, tapped, or disrupted.

“There are about 550 subsea cables around the world – they’re the internet, and nobody fully knows exactly what happens if you take all of them out,” Declan Ganley, chief executive of Rivada Space Networks, said at the conference on Friday. “But for about $60 million in cash, it can be arranged and this is really a 9/11 event, but far more impactful… If you take the internet out and you take the ability to operate cyber off of your opponent, who’s in the stronger position after that event?”

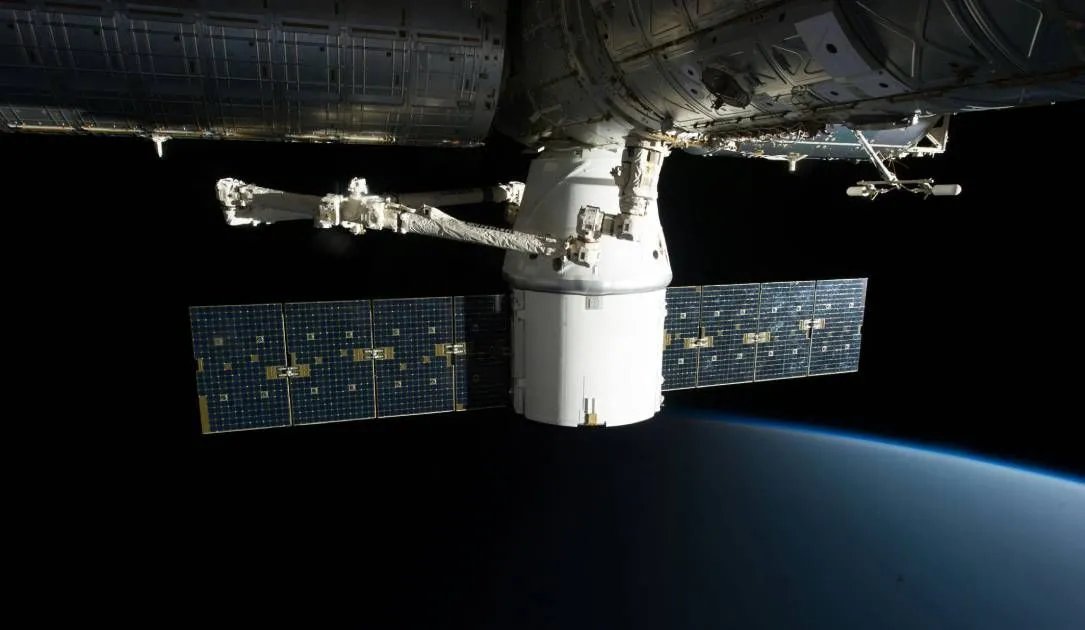

Rivada is deploying a 600-satellite constellation this year and next to make sure that doesn’t happen. “Let’s say Beijing and Moscow at the same time decided they were going to do a joint operations, so they’re going to move on somewhere in Europe and Taiwan at the same time,” he said. “If I was them, I would cut all the subsea cables. I’d arrange for fishermen to cut the cables.”

His point was unsettlingly simple: the barrier to catastrophic disruption may be far lower than most people assume. Sever those lines, he argued, and modern warfare could suddenly revert to brute force.

“Take away the eyes and ears of your opponent, take away the strength that they play to, and make them weak,” he said. “Given that we have all of this dependence upon these arteries of cyber, which are those subsea cables, which is a high concentration of risk, space has to be an alternative.”

The ‘outernet’ solution

Ganley’s answer is what he calls an “outernet” — a satellite communications network designed to operate independently of terrestrial infrastructure. Unlike conventional satellite internet, which ultimately connects back to ground stations and cable networks, this system would remain functional even if those systems were destroyed.

The distinction, he argued, is crucial.

“Now everybody may think, well, Starlink will solve the problem,” he said. “It won’t, because Starlink is connected to the ground gateways, the subsea cables, the same as every other internet solution. Starlink is more like a cellphone tower, but in space. It certainly can use inter-satellite links to pass you on, but ultimately it’s an internet solution.”

In other words, even the systems that seem most futuristic are still tethered to Earth in vulnerable ways.

No one knows exactly how much damage would trigger a cascading collapse — whether losing 30 percent of cables would do it, or 50 percent, or some unknown threshold. But somewhere, Ganley warned, that tipping point exists.

“We don’t know… actually nobody knows… but there is some critical point where the whole thing falls over,” he said. “So the alternative and the approach to cyber in space is create a network that can survive that event or at least survive it long enough that you have the advantage of minutes, hours, days, maybe months of keeping comms up so you can continue cyber even in the event of something like that happening. Right now you cannot do it. That’s what we’re focused on.”

The idea reflects a broader shift in defense thinking: less faith in preventing disruption, more emphasis on surviving it.

A new theater of conflict

Other Munich speakers warned that the diplomatic guardrails for space are lagging dangerously behind the technology. Nina Armagno, former director of staff at U.S. Space Command, noted that Washington maintains crisis hotlines with Moscow for space operations — but not with Beijing. In a domain where a misunderstood satellite maneuver could be mistaken for an attack, that absence carries real risk.

Taken together, the conversations in Munich pointed to a stark conclusion: space is no longer merely supporting conflicts on Earth. It is becoming a primary theater of competition in its own right — one where civilian systems, commercial platforms and military capabilities are tightly intertwined and nearly impossible to separate.

There was an echo here of the early internet: technologies built for openness and efficiency now being hurriedly retrofitted for security after adversaries exposed their vulnerabilities.

Whether democracies can move fast enough remains an open question. Building resilient satellite constellations takes years and enormous investment. Disrupting them may require far less: a missile test, a cyber intrusion, or a carefully timed act of sabotage.

In that sense, the race unfolding in orbit is not really about exploration anymore. It is about endurance — making sure the digital nervous system of modern life keeps functioning when, not if, it comes under attack.