WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court on Monday will weigh whether a devout Rastafarian can bring a damages claim against Louisiana prison officials who cut his dreadlocks in violation of his religious rights.

The court, which has a 6-3 conservative majority, is often solicitous toward religious claims, although the bulk of recent cases have involved cases brought by conservative Christians.

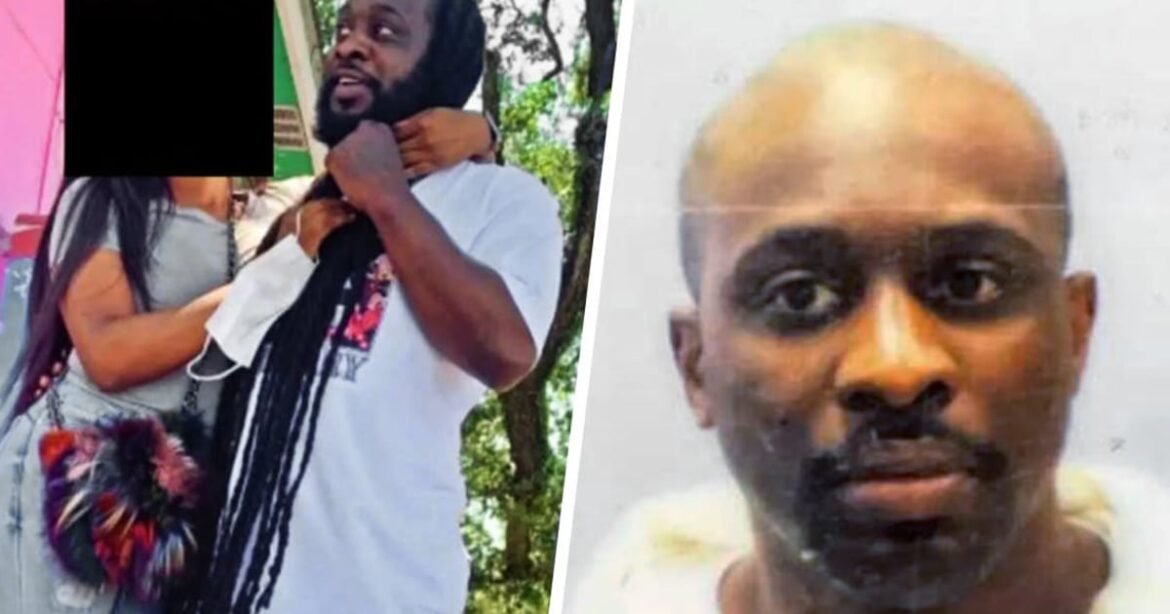

Prior to the 2020 incident at the Raymond Laborde Correctional Center, Damon Landor had not cut his hair for almost 20 years, following a practice known as “the Nazarite vow.”

Landor was serving a five-month sentence on a drug-related charge when he was transferred to the facility.

Over his objections, a corrections officer handcuffed him to a chair while two others shaved his head.

“In an instant, they stripped him of decades of religious practice at the heart of his identity,” Landor’s lawyers wrote in a court filing.

The officers went ahead even though Landor had shown them a copy of a binding court ruling that said it would be a religious rights violation to cut a Rastafarian’s dreadlocks.

Landor subsequently filed suit against the state. The claim at the Supreme Court revolves around whether he can claim money damages under a law called the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, or RLUIPA.

The state, represented by Attorney General Elizabeth Murrill, a Republican, has conceded that Landor’s lawsuit raised claims “antithetical to religious freedom and fair treatment of state prisoners” and said the prison system has since changed its grooming policy.

But she argues that damages are not warranted.

Landor’s lawyers are asking the Supreme Court to rule that damages should be allowed under RLUIPA, citing a ruling in 2020 that said damages are available under a similar law called the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Without damages, the protection afforded by RLUIPA would “ring hollow,” they wrote.

The state says the outcome is not determined by how the court ruled in the 2020 case in part because that dispute involved federal, not state, officials.

Lower courts ruled in favor of the state, prompting Landor to turn to the Supreme Court.