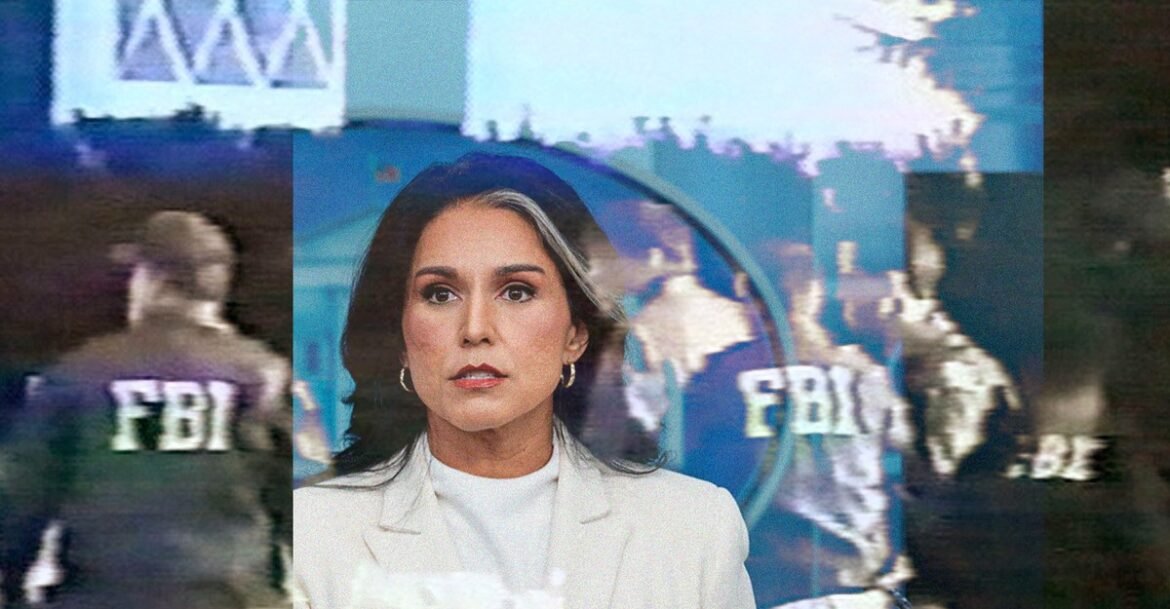

Throughout Donald Trump’s first term, his third campaign, and the first 10 months of his second term in office, he and his allies warned darkly of a “deep state” seeking to thwart his every move. In an address to the National Conservatism Conference in September, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard said that “leaders in the intelligence community”—the massive bureaucracy she runs—are among the “traitors to the Constitution” who have tried to undermine the president because they oppose his policies.

This kind of public invective is par for the course in the Trump administration. But these attacks have generated real action: Gabbard has revoked security clearances of supposed Trump opponents by the dozen and fired high-ranking staff while the Justice Department busies itself with dismissing civil servants and prosecuting the president’s enemies. Now Gabbard’s agency, which coordinates among the different elements of the intelligence community, is advocating for legislation that would transfer significant authority over counterintelligence to her office and away from an FBI that her staff has portrayed as the home of a traitorous deep state. The legislation, introduced by House Intelligence Committee Chair Rick Crawford and tucked into a yearly bill authorizing intelligence activities, would establish the Office of the Director of National Intelligence as the lead agency in charge of counterintelligence. The House and Senate must now hash out the shape of the final bill.

Counterintelligence, the work of catching foreign spies, has long been the FBI’s bailiwick, and the bureau is vehemently opposed to the transfer. But Gabbard’s office seems to believe that the FBI’s Counterintelligence Division is irredeemably politicized—which is to say anti-Trump. The contours of this turf war are illustrated in a memo with comments from the National Security Council, the FBI, and Gabbard’s office that we have reviewed and that is circulating among government agencies potentially affected by the legislation. “If we do nothing,” the memo warns, “the same deep state actors who have egregiously weaponized counterintelligence for political purposes will be empowered.” The memo was distributed among government agencies last week as part of a process of soliciting feedback on the draft legislation, which the House Intelligence Committee approved a version of in early September.

For now, at least, Gabbard’s quest to take control of counterintelligence seems to lack the allies it would need for success. Complicating her bid is the fact that the FBI, the agency she seeks to displace, is itself under the leadership of fellow Trump loyalist Kash Patel—who once referred to the agency as “one of the most cunning and powerful arms of the Deep State.” The onetime foes of the deep state now run the place, and their allegiances to conspiracy theories are proving flexible when it comes to protecting their own fiefdoms. Patel’s ominous warnings of anti-Trump vipers lurking within the bureau apparently weren’t enough to prevent him from allowing the FBI to defend its own turf. Gabbard, in contrast, may have just discovered that ominous warnings of deep-state conspirators aren’t enough to persuade the White House to hand her more power.

For months now, Gabbard has accused current and former government personnel who investigated Russia’s interference in the 2016 election of taking part in a “years-long coup” against Trump. FBI counterintelligence played a central role in efforts to stop Russia from meddling in the presidential campaign and to identify the perpetrators.

In Trump’s telling, FBI agents are among the core peddlers of the “Russia hoax”—the idea that Democrats and the federal government engineered lies about Russian election interference to falsely tarnish Trump’s 2016 campaign. No wonder, then, that Gabbard is proposing to take control over much of the FBI’s counterintelligence work. But the White House, thus far at least, seems cool to a major reorganization. “The administration is opposed to the transfer of counterintelligence responsibilities from the FBI to the ODNI,” a senior administration official told us.

Gabbard has struggled to find her place in the president’s inner circle. Over the summer, her influence had so eroded that one Trump ally called her a “nonplayer.” Trump has also told aides and allies that he’s not sure the Office of the Director of National Intelligence is even necessary.

Gabbard has attempted to raise her stock by declassifying documents that she claims allege a grand conspiracy by Trump’s enemies to undercut him in 2016. But she is still on shaky footing, and has arguably erred in trying to take on the FBI, a far larger and more bureaucratically powerful organization than the one she runs. Despite Gabbard’s impressive-sounding title, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence is a relatively small agency. It dates back only to 2004, when it was established as part of the post-9/11 project of improving cooperation among intelligence agencies, and has never really managed to consolidate its authority over the older and better-established centers of bureaucratic power that make up the nation’s intelligence community.

Today, the FBI appears uninterested in giving up any of that power. “This proposal would significantly duplicate and confuse constrained resources,” the FBI diplomatically writes in the memo, which includes additional cautionary statements from the National Security Council. The New York Times recently reported on a separate letter to Congress sent in mid-October in which the bureau warned of “serious and long-lasting damage to the U.S. national security” should the intelligence director’s office take over counterintelligence authorities.

Asked about these critiques, a spokesperson for the House Intelligence Committee responded that the memo circulated among agencies was “out of date” and that the committee has continued to “incorporate remedies to points of concern” as the bill moves forward. The legislation “does not move significant parts of the FBI’s counterintelligence mission” to Gabbard’s office, the spokesperson said; rather, the bureau’s Counterintelligence Division would be “buttressed” by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Gabbard’s office sent us a joint statement with the FBI, reading, “The ODNI and the FBI are united in working with Congress to strengthen our nation’s counterintelligence efforts to best protect the safety, security, and freedom of the American people.”

Counterintelligence can be a tricky area to define. Essentially, it’s spy versus spy—the work of catching foreign agents and disrupting espionage against the United States. James Jesus Angleton, who led the CIA’s effort to identify Soviet moles during the Cold War, famously described the practice as “a wilderness of mirrors.” Now the FBI performs the bulk of counterintelligence investigations. As part of this work, specially trained FBI agents cultivate sources in foreign intelligence agencies. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence, which is largely an administrative agency, has no comparable investigative arm, something law-enforcement officials and intelligence veterans we spoke with were quick to point out.

China is undoubtedly the main focus of FBI counterintelligence operations. In March of this year, an investigation by the FBI and Army counterintelligence led to the arrest of two active-duty U.S. soldiers accused of giving classified information and weapons designs to China. And in July, the Justice Department charged two Chinese nationals with spying on U.S. Navy bases and helping to identify service members whom China’s security service might try to recruit.

Crawford’s case for the legislation has focused not on fighting the deep state, but on promoting the bill as a means of centralizing the nation’s counterintelligence work at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and cutting through “bureaucratic red tape.” According to the latest public version of the bill, Crawford’s proposal would create a new “National Counterintelligence Center” under the Director of National Intelligence, which would “lead and direct” the government’s spy-hunting work. The head of this new center would have the power to direct different agencies such as the FBI and CIA on how to use their counterintelligence authorities, and require agencies to get sign-off from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence before moving forward with their own plans. The legislation also gives Gabbard’s office insight into the FBI’s process of investigating leaks or mishandling of classified information.

Supporters of Crawford’s legislation say that the FBI has bogged down counterintelligence work by treating it as a law-enforcement matter. The bureau’s job is to gather evidence to bring criminal charges, which is fine as far as that goes, they say. But—in their argument—rampant espionage by China, which includes the theft of valuable technical research from U.S. corporations and universities, demands a strategy to disrupt and deter those adversaries, not one that is always premised on bringing cases to court. “The counterintelligence threat is very real,” the House Intelligence Committee spokesperson said. “This is not politics; this is about national security and the safety of Americans in the homeland.”

Michael Feinberg, a former FBI agent who spent much of his career in the bureau’s Counterintelligence Division, questioned this characterization of the FBI’s work. (Feinberg was pushed out of the FBI earlier this year as part of the agency’s effort to purge agents considered insufficiently loyal to Trump.) “Prosecutions represent only one tool used by the organization to thwart foreign spies,” he said over text. “Both on its own and with other intelligence community partners, the FBI engages in a wide swathe of activities—most never revealed to the public—to keep our nation’s secrets safe.”

Crawford and Gabbard appear unlikely to get the changes they want, at least in the near term. But with Trump in the Oval Office, sometimes all it takes to turn things around is for a person with a convincing pitch and an enmity for the deep state to sell their idea to the president. In a government stocked with combustible personalities and conspiracy theorists, no proposal, however far-fetched, can truly be declared dead for long.