Patient characteristics at baseline

All patients with ASyS and SSc were treated at the University Hospital of Düsseldorf after written informed consent according to CARE guidelines and in compliance with Declaration of Helsinki principles. Sampling of patient material was performed, and ethical approval for our biobank was obtained (2022-2189 and 2023-2561). Treatment was conducted as part of a compassionate use program without a specific research protocol.

All patients with ASyS were positive for anti-Jo1 autoantibodies. Three out of five patients also showed autoantibodies against Ro-52. Each patient with ASyS previously did not respond to at least four immunomodulatory medications, including RTX. Detailed characteristics of patients with ASyS at baseline are shown in Table 1.

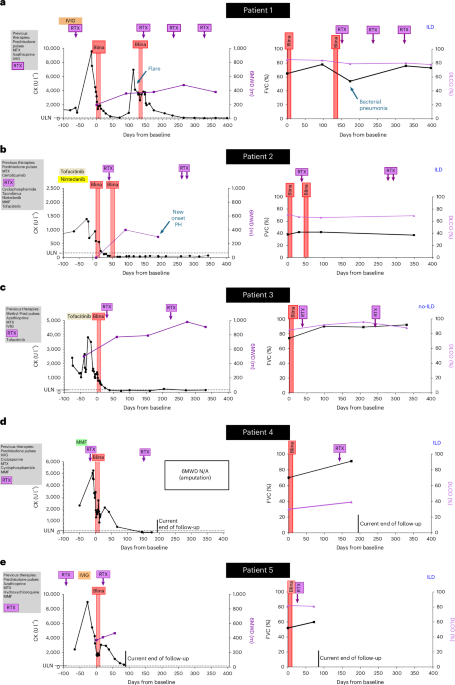

Patient 1 (ASyS) was a 65-year-old woman diagnosed with anti-Jo1+ ASyS in 2022. She previously experienced an infection with hepatitis B. Initial symptoms included muscle weakness in the legs, neck and shoulders, dyspnea, mechanic’s hands and weight loss. Laboratory tests showed elevated CK, and MRI revealed severe myositis of both quadriceps muscles. She did not achieve the desired treatment response after treatment with methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine, high-dose IVIG and RTX (last infusion 2 months before baseline; B cells depleted in peripheral blood), with repetitive flares that required multiple pulses of prednisolone. She developed ILD on HRCT with a non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) pattern and declining FVC and diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide-alveolar volume (DLCO-VA).

Patient 2 (ASyS) was a 36-year-old man diagnosed with anti-Jo1+ ASyS in 2022, after initial diagnosis of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis in 2021, which had been treated with MTX and certolizumab. At the time of diagnosis of ASyS, he presented with muscle weakness in arms and shoulders with elevated CK levels, mechanic’s hands and recurrent arthritis of hands and knees. Treatment with RTX was initiated in 2022. During treatment with RTX, he developed ILD with an NSIP pattern and myocardial involvement as evidenced by CMR imaging with increased native global T1 times and ECV. Despite treatment with cyclophosphamide followed by MMF and tacrolimus, the ILD progressed rapidly, requiring oxygen supplementation. Tacrolimus was stopped and nintedanib initiated. Subsequently, flares of arthritis required repetitive pulses of prednisolone. At first presentation in our department in October 2023, he demonstrated severe and progressive dyspnea (NYHA III/IV). We replaced MMF with tofacitinib, resulting in better control of arthritis but not of myositis, pulmonary and cardiac involvement, despite additional uptitration of prednisolone.

Patient 3 (ASyS) was a 47-year-old man diagnosed with anti-Jo1+ ASyS in 2020. Symptoms included bilateral quadriceps weakness, elevated CK levels and mechanic’s hands. His CMR imaging did not demonstrate evidence of myocardial involvement at that time. He exhibited persistent serological activity and progressive muscle weakness despite treatment with MTX, azathioprine, high-dose IVIG and RTX and repeated courses of high doses of prednisolone. In 2024, he presented at our department with highly active myositis with necrosis on histology. He was unable to work and required assistance with activities of daily living. He demonstrated no signs of ILD on HRCT. On follow-up, CK levels increased further. He also presented with an active, enlarging ulcer on his lower right leg. Polymerase chain reaction testing revealed positivity for M. kansasii, and a triple antibiotic treatment was initiated that induced gradual healing.

Patient 4 (ASyS) was a 48-year-old woman diagnosed with anti-Jo1+ ASyS in 2020, after an initial, external diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis, which was treated sequentially with leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, ixekizumab and apremilast. At the time of diagnosis of ASyS, MRI scans showed generalized myositis of all thigh muscle groups and myocarditis. ILD was detected in 2022. Treatment with MTX, IVIG, MMF, cyclophosphamide, ciclosporin and RTX (last infusion 1 week before baseline) failed to provide sufficient disease control, with recurrent flares of myositis, mechanic’s hands and progressive dyspnea. During these therapies, she developed pneumocystis jirovecii-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) requiring invasive ventilation, cardiac decompensation and severe deep vein thrombosis, leading to amputation of the right leg just below the knee. At first presentation in our department in 2025, HRCT demonstrated ILD with an NSIP pattern. Her CMR imaging showed increased native T1 values. Her FVC progressively declined, her demand for supplementary oxygen increased and she showed signs of active myositis on MRI and muscle biopsy.

Patient 5 (ASyS) was a 50-year-old woman with anti-Jo1+ ASyS diagnosed in 2020. Her initial symptoms included myalgia, arthritis and skin rash. ILD was detected in 2021. She experienced repetitive flares under treatment with azathioprine, MTX and hydroxychloroquine, requiring repetitive cycles of glucocorticoid pulses. After referral to our department in 2023, treatments with MMF, RTX (last infusion 3 months before baseline) and IVIG did not provide sufficient disease control, with repetitive flares of myositis, skin rash and progressive dependency on assistance to manage daily activities. She developed severe pneumonia with ARDS, requiring invasive ventilation and veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in June 2024. Subsequent MRI and muscle biopsy demonstrated active myositis, and her HRCT showed progression of ILD with further declines of FVC.

All patients with SSc were diagnosed with dcSSc. Four patients were positive for autoantibodies against topoisomerase 1, and one patient was positive for anti-fibrillarin autoantibodies (patient 10). All patients demonstrated widespread skin fibrosis, ILD and SSc with primary heart involvement (SSc-pHI). Each patient failed previously to respond to at least three different immunmodulatory/antifibrotic drugs (Table 2).

Patient 6 (SSc) was a 65-year-old man diagnosed with dcSSc in 2006. He developed progressive ILD with declining FVC and DLCO despite treatment with cyclophosphamide, azathioprine and MMF. He was admitted to our department in May 2024 with an mRSS of 21, TFRs, an FVC of 52% and dyspnea NYHA III. CMR imaging demonstrated globally increased native T1 values and ECV according to local reference standards, consistent with SSc-pHI. His hsTnT levels were increased.

Patient 7 (SSc) was a 52-year-old man diagnosed with dcSSc in 2023. In addition to SSc, he was diagnosed with lung emphysema associated with extensive smoking (80 pack-years), which he stopped in May 2024. He presented to our department in January 2024 with suspicion of SSc-pHI and progressive skin fibrosis despite previous therapies with hydroxychloroquine, MTX and MMF. His mRSS was 22, his CRP level was elevated and he had multiple TFRs. HRCT demonstrated progressing bibasilar reticulations in addition to his emphysema. FVC was 80%. CMR imaging demonstrated SSc-pHI with increased T1 times and ECV. His hsTnT levels were elevated, and he lost 15 kg of body weight within the previous 12 months.

Patient 8 (SSc) was a 56-year-old man diagnosed with dcSSc in 2020. He developed progressive skin fibrosis, ILD and SSc-pHI. He was admitted to our department in August 2024 after failure of MMF, MTX, nintedanib and RTX (last infusion 5 months before baseline, still B cell depleted in peripheral blood at baseline). His mRSS was 28, and he had TFRs and progressive pulmonary fibrosis on HRCT with an FVC of 52%. CMR imaging showed increased T1 values, ECV and LGE; hsTnT levels were elevated. He gradually lost 10 kg of body weight over the previous 4 years.

Patient 9 (SSc) was a 46-year-old man diagnosed with dcSSc in 2022. Skin fibrosis progressed despite treatment with MTX, cyclophosphamide and RTX (last infusion 7 months before baseline; B cells partially depleted in peripheral blood). He was admitted to our department in 2024 with an mRSS of 38 and multiple TFRs. An HRCT scan demonstrated new onset of SSc-ILD (after a negative HRCT 6 months prior) with a rapid decline in FVC to 68%. His CMR imaging demonstrated new onset of biventricular systolic dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction (LV-EF) of 41% and right ventricular ejection fraction (RV-EF) of 37%), globally increased native T1 and T2 values as well as diffuse patchy LGE (after almost normal CMR imaging 6 months prior). Furthermore, he presented with a new left ventricular hemiblock and supraventricular tachycardia and increased hsTnT levels. Moreover, he gradually lost 9 kg of body weight within 2 years.

Patient 10 (SSc) was a 46-year-old man diagnosed with dcSSc in 2024. He also fulfilled the criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. He developed progressive skin fibrosis and progressive SSc-ILD and SSc-pHI despite previous treatment with MMF, cyclophosphamide, nintedanib and RTX (last infusion 4 months before baseline, still B cell depleted in peripheral blood). He was admitted to our department in 2025 with an mRSS of 23, multiple TFRs, rapid declines in FVC (54%) and DLCO and evidence of SSc-pHI with globally increased native T1 values on CMR imaging and elevated hsTnT levels. Moreover, he had active myositis of the pelvic and quadriceps muscles as demonstrated by MRI and muscle biopsy with elevated CK levels. He lost 18 kg of body weight since his diagnosis of SSc.

Induction therapy with blinatumomab and teclistamab

Blinatumomab or teclistamab therapy was offered via a compassionate use program for critically ill patients according to the Arzneimittelgesetz Section 21/2 and the Arzneimittel-Härtefall-Verordnung Section 2, which allows experimental treatment if (1) patients are afflicted by a severe, potentially life-threatening disease, (2) patients have failed on previous standard-of-care treatments and (3) a scientific rationale exists—that the respective treatment potential might be efficacious in the disease. Interventions were reported to the legal authorities. Use of patient data and biomaterial from this study was covered by licenses 2022-2189 and 2023-2561 of the institutional review board of the Heinrich-Heine University of Düsseldorf. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Council for Harmonization. All participants gave written informed consent for all the procedures and the data sharing according to CARE guidelines and in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. No commercial sponsor was involved.

In all patients, classical and targeted synthetic and biologic DMARDs and antifibrotics were discontinued at least 1 week prior to the first dose of blinatumomab and teclistamab. Blinatumomab and teclistamab were applied as part of compassionate use programs. Patients received no compensation.

Blinatumomab has a short half-life of approximately 2.1 hours38 and was administered by continuous intravenous infusion in a dosage of 9 µg per day for 5 days, followed by 14 µg per day for 7 days (in total, 143 µg per cycle) (Extended Data Fig. 1). Data show the rapid decline of B cells after infusion: 50% after the first hour and 90% after 4 hours, leading to undetectable B cells after 2 days39. Treatment was started in an inpatient setting. After day 7, the therapy was continued in an outpatient setting. Teclistamab was subcutaneously injected at doses of 0.06 mg kg−1, 0.3 mg kg−1 and 1.5 mg kg−1 every other day in an inpatient setting with potential extension of the intervals up to 9 days, followed by two further cycles of teclistamab at 1.5 mg kg−1, each administered at 2-week intervals (Extended Data Fig. 1). Premedication for both TCEs followed the established protocols of the manufacturer and consisted of 1 g of paracetamol orally, 2 mg of clemastine intravenously and 20 mg or 16 mg of dexamethasone intravenously for blinatumomab and teclistamab, respectively.

Maintenance therapy with RTX

To prevent redifferentiation of autoantibody-producing cells from CD20+ B cell precursors after the last application of TCE, we administered RTX in doses of 1 g per infusion. Determination of the dosing schedule for RTX was part of our compassionate use program, considering the pharmacokinetics of the TCE, the serological response and the clinical course, with adaptations based on insights gained from ongoing patients.

Patient 1 initially did not receive RTX, as her CD20+ B cells were still depleted at baseline due to a previous application of RTX. In patients 2, 3, 4 and 5, we administered RTX after the first cycle of blinatumomab, in part based on the experiences in patient 1 (Fig. 1). RTX administration was repeated every 3−5 months in order to maintain B cell depletion.

In patients with SSc, we administered maintenance therapy with repetitive doses of RTX starting 2 weeks after the last teclistamab dose. As this dosing schedule resulted in complete suppression of peripheral B cell counts and induced progressive decline of autoantibodies in patient 6, we applied this dosing scheme to all other patients with SSc as well (Extended Data Fig. 1)

In patients treated with teclistamab, aciclovir and cotrimoxazole were administered as infection prophylaxes, and 20−30 g of IVIG was infused when serum IgG dropped below 400 mg dl−1 for the first time and then every 4−6 weeks.

Clinical assessment

All patients were monitored using standard clinical examination, laboratory parameters, pulmonary function testing (FVC and DLCO), 6MWT, NYHA classification, CMR imaging and HRCT. Gender was assessed using self-reports. Assessments of patients with ASyS included, additionally, MMT8, total score including both sides and axis, TIS, muscle MRI and muscle biopsy. Assessments of patients with SSc included, additionally, mRSS, TFR, EUSTAR-AI and skin biopsies. Anti-Jo1 and anti-topoisomerase 1 IgG antibody levels were measured by immunoblot (IgG EUROLINE; Euroimmun) and ELISA (EA 1599-960G and EA 1661-960GG; Euroimmun), respectively.

Muscle and skin histopathology and immunofluorescence staining

Immunohistochemistry stainings were performed on sequential muscle cryosections with anti-CD3 (clone ZM45, 1:100; Zeta Corporation), anti-CD8 (clone C8/144B, 1:50; Agilent Technologies), anti-CD163 (clone ZM29, 1:200; Zeta Corporation), anti-MHC-I (clone W6/32, 1:800; Agilent Technologies) and anti-membrane attack complex C5b-9 (clone aE11, 1:50; Agilent Technologies) antibodies, using the avidin-biotin complex technique.

Immunofluorescence stainings of muscle cryosections were performed with anti-CD19 (302202, 1:50; BioLegend) antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (sc-3598, 1:800; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Stainings of skin paraffin sections were performed with the anti-BCMA (ab5972, 1:400; Abcam) antibody. For immunofluorescence, nuclei were stained with DAPI (sc-3598, 1:800; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For immunohistochemistry, sections were co-stained with anti-CD3 (clone ZM45, 1:100; Zeta Corporation) antibodies.

The immunohistochemistry interpretation was corroborated by at least two independent observers.

CODEX staining of skin paraffin sections was performed as previously described39. The primary antibodies for CODEX are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Five micrometers of skin formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections were incubated on 65 °C for 1 hour, deparaffinized by xylene and rehydrated by a series concentration of ethanol. Epitope retrieval was performed with Tris-EDTA (pH 9) using a pressure cooker. To quench the autofluorescence, the tissue sections were bleached by using high-power LED panels in the bleaching solution as previously described40,41,42. After blocking with CODEX Blocking Buffer (Akoya Biosciences), sections were incubated overnight with primary antibody cocktail in Staining Buffer (Akoya Biosciences) at 4 °C. The stained tissue was fixed and stored following the instructions provided by Akoya Biosciences.

CODEX multicycle imaging was performed using a PhenoCycler-Fusion 2.2.0 equipped with a ×20 air objective (Akoya Biosciences). The barcoded reporter oligonucleotides labeled with ATTO550 and ATTO647 (biomers.net GmbH) were used to capture up to two protein stainings each cycle. Nuclear images were obtained by DAPI staining for every cycle. Aligned multiplexed images were generated in a QPTIFF format from the PhenoCycler-Fusion system. Figure 2f and Extended Data Figs. 5–7 were generated with Phenochart 2.2.0.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism version 5.03.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Deepl.com in order to improve language and grammar. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.